Erika McEntarfer in, mostly, her own words

The rust belt resonates with labor historians, but we generally don’t use the term. Years ago our friend Kim Hill, then at the Center for Automotive Research, CAR, in Ann Arbor, suggested it denigrates the progress being made in many of those communities, asking if we had visited Ann Arbor recently. We hadn’t, and respect his opinion.

But Erika McEntarfer, former commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, described the region where she grew up in western New York as the rust belt in a recent talk, sponsored by the Levy Institute, on the importance of official data. Her community was “struggling to find its way economically…with unemployment very high and jobs very scarce.”

She spoke at Bard College’s Olin Auditorium, where she had taken her first economics class as an undergraduate. Economics was not her intended field, and she admitted she had thought it had “something to do with the stock market.”

But that class changed her life, giving her “the tools to understand the things in the world that have really puzzled me…. I honestly didn’t realize…how much economic disparity exists in this country…how some regions were prospering and gaining wealth right alongside places that were struggling.” Instead of a field focused on investment practices, she found economics to be a “discipline focused on questions of prosperity, economic growth and inequality. I was sold. I decided that I would become an economist.”

Originally intent on teaching, she turned down an academic job when she became “fascinated by a startup research lab at Census,” that was working to leverage recent gains in computer power that would allow extant administrative data to be reworked for use in federal statistics. Her advisor may have thought her mad for passing on academia, but she joined Census in 2002 after receiving her PhD from the University of Virginia. There she “found the mission of putting data in the hands of people who can use it to improve their communities and make their lives better, more and more gratifying.” Her team’s research was being used in economic development planning, disaster relief, and placing students in good jobs. “If you want to leave the world a better place than you found it, one path to doing so is serving the American people and trying to make life here better for everyone in big ways and small.”

She spent a year as labor economist at the White’s House’s Council of Economic Advisors. The council was founded in 1947 to provide “objective and non-partisan advice and perspectives to the President and senior White House officials on economic research, policy and the state of the economy.” It’s standard practice for the BLS commissioner to brief the council on the upcoming employment report on the Thursday afternoon preceding its release, and Erika reports during her tenure council members “ate way too much chocolate and pizza [as they] stayed up way too late wordsmithing the blog” that would be posted the next day following the release of the payroll report. “…Ultimately, our job was to give the President a narrative that he could use to inform the American public, and really the world, about what was happening in the US economy.”

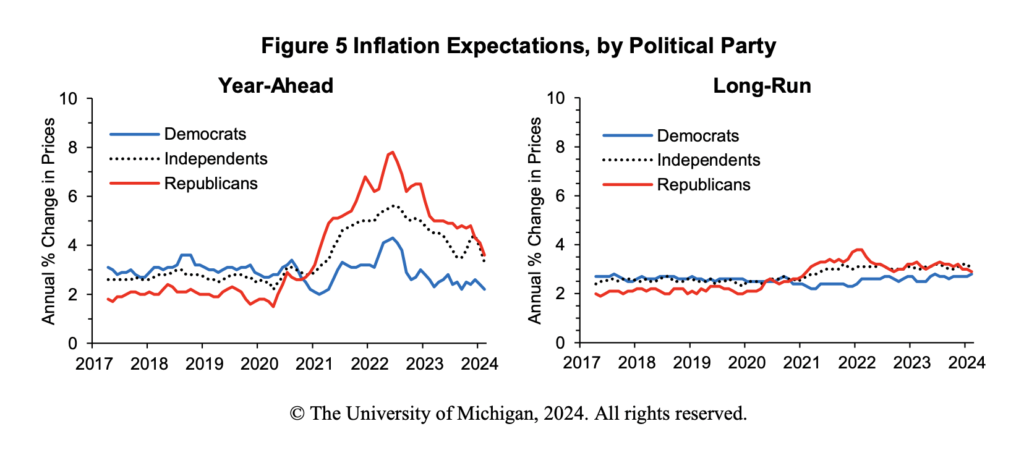

When she joined the council in 2022, inflation was peaking, the labor market was still struggling, economic sentiment remained grim, and every newspaper was forecasting a recession. Importantly, the council used the monthly job reports as they are intended to be used, as warnings of a potential cycle change. But instead of the predicted recession, at that time the labor market began to recover.

In 2023, when the term of prior BLS commissioner William Beach was ending, McEntarfer was asked to submit an application. To her surprise she received the nomination. (By the way, Beach, a Trump appointee, is working across party lines. He has been outspoken about McEntarfer’s dismissal, and characterized an economic explanation made by one of Trump’s top advisors on employment revisions as “the strangest thing in the world.” It’s worth a look!)

Although McEntarfer dreaded the confirmation process, through her work on a number of committees she was “known among officials of both parties as a non-partisan government economist” and was “confirmed faster than any BLS nominee in recent history.” JD Vance and Marco Rubio were among an unusual thirty-eight Republicans who supported her nomination in the eighty-six to eight confirmation vote.

McEntarfer arrived at the Bureau of Labor Statistics with plans to extend the work she had done at Census to modernize data processes, and, like Erica Groshen, also a former BLS commissioner, was dedicated to getting accurate labor data out more quickly. For example, with proper funding the monthly payroll reports could be benchmarked each quarter, which would narrow the size of the benchmarks and tone down the leadup to the currently annual benchmark. By the way, that chatter is a new thing. We’ve followed the benchmarks since 1997, and only in the last few years have they become such a controversial event.

The public needs to be better educated about the BLS’s priorities. Despite a full page of filing instructions, including electronically, for businesses participating in the monthly employment survey, we have heard from a reliable source that following McEntarfer’s dismissal a national broadcaster reported response forms are still faxed to the BLS. Some small operations may use a fax, but large firms are using “big electronic collection systems.”

These misconceptions about BLS processes, economic narratives really, are fueling the push to replace official BLS data with data scraped from the private sector. When this came up in the Q&A, McEntarfer called private-sector data a great compliment to BLS data, adding that some of the biggest supporters of the established BLS reports are the very people producing private-sector databases. Without a comparative standing series, the reliability of their own work is in question. Nela Richardson, chief economist at ADP, is persuasive on the complementary nature of the different reports, and Levy’s Pavlina Tchernava, who participated in McEntarfer’s talk, provided additional background.

McEntarfer also noted the private data sector can be very expensive, which of course would exclude smaller institutes.

As we mentioned above, it’s standard practice for BLS staff to go over each upcoming employment report with the current administration’s Council of Economic Advisors on the Thursday afternoon prior to Friday’s release of the data.*

Recounting August 1st, the day of her dismissal, McEntarfer told her audience that when she spoke with the council on Thursday, and with the Secretary of Labor on Friday morning, both prior to the release of the report, they asked “really normal questions,” about the revisions. The revisions are caused by late responders, and one question concerned a possible skew by size of firm as the second and third closings, the BLS term for the process, were collected. Many of us have wondered about that, but apparently it’s a broad trend.

While the size of the revisions were unusual, they were not “without precedent.” In her discussions with the council and secretary, McEntarfer noted revisions can signal a turn in the cycle, such as when the “labor market slows suddenly…at the start of a recession,” but suggested immigration policy and tariff uncertainty may have put pressure on hiring in the spring, so the markdowns to May and June job gains “didn’t necessarily mean” the economy was going into recession.

Saying, “let’s face it, this isn’t the kind of news any administration wants to hear,” she described a room full of “long faces.” But when she asked the council for further questions there were none, so they all “moved on.”

Following those meetings McEntarfer had no sense anyway was wrong. When she received an email from a reporter asking her if it were true Trump had just fired her, her first thought was no. “[This] wasn’t the first time Trump had accused the Bureau Labor Statistics of cooking the books…. I thought it was impossible because firing your chief statistician is a dangerous step… an attack on the independence of an institution arguably as important as the Federal Reserve for economic stability.”

Then she noticed an earlier email she had missed: “On behalf of President Donald J. Trump I am writing to inform you that your position as Commissioner of Labor Statistics is terminated effective immediately. Thank you for your service.”

The 2,000 BLS employers, down from 2,5000 a few years ago, are civil servants. All except one, that is, the commissioner who is appointed for a fixed four-year term and confirmed by the senate. In a discussion with Steve Odland of the Conference Board, Erica Groshen made it clear that the fixed term distinguishes those serving at the “pleasure of the president,” and advocating for a political agenda, from an appointee with the technical skills needed to administer an agency whose work we all, including Congress, have deemed a necessary public good.

I doubt anyone in the audience expected McEntarfer to be humorous at this point in her talk, but she was, saying just as she saw the email from the presidential personnel office, her phone “exploded.” Of course all the major networks were calling, and so was her mother who had gotten a call from George Stephanopoulos who was trying to reach Erika. In her words, she had always been careful not to bore her family with the details of her wonky job, but now the whole world was talking about it.

In her nationwide travels, Erika had discovered that many have never heard of the BLS, or know that its commissioner is approved by the Senate. In her mind, “That’s really how it should be. You should get to live in a country where you do not have to know who the chief statisticians are, and worry that they are okay.”

McEntarfer’s “best and dearest hope” is that the administration’s interference will end with her firing, and suggested we study what happened in countries like Greece and Turkey when economic reports were manipulated. For example, the Argentinian government went after private sector vendors who tried to replicate missing data. Of course borrowing rates went up; anyone following our deficit knows we cannot afford that.

She called that a list we don’t want to join, and we’ll add there’s another unfortunate crew no one wants to be part of, the presidents who attempted to pressure the BLS to rig their data: The current president’s name is now up there with Herbert Hoover and Richard Nixon. History may not be kind.

McEntarfer vouched for the “accuracy and independence of the work of the agency up until the moment I was fired, and was unwilling “speculate” about the plans of the current administration. She did tell her listeners that she has worked with acting commissioner William Wiatrowski for eighteen months, calling him among the “finest public servants” she has known.

Despite the uncertainty of the current moment, (list of senior vacancies here) McEntarfer believes the damage to the BLS can be repaired, and knows that “those still within the agency have not stopped working on behalf of the American public.” McEntarfer read from a statement sent to the press around the time of her dismissal by BLS employees anonymously, the only way they can speak out these days. The memo noted that commissioners don’t “cook,” the number – they don’t even see them until they are complete. We’ll add that’s something that, oddly, the Secretary of Labor may not understand.

That memo suggested that the “real goal is to discredit independent statistics, slash budgets and [force] federal workers into silence. But BLS staff will not be intimidated. We will publish reliable data, no matter how inconvenient the results. The numbers will remain accurate and nonpartisan, and if that ever changes, the professionals will tell you.”

Measured, truthful, and confident, Erika spent her youth in the deindustrialized landscape, and made her career plans when she recognized a way to improve outcomes with accurate data. In closing she said she hoped it was clear how much she loved being a public servant, that she has devoted her entire career to helping people make better policy choices through reliable data, and “sincerely wishes” her time at the BLS had not been cut short.

Her career is far from over, and we look forward to her next steps.

* Data point: That’s generally the first Friday of the month, but the formula specifies the third Friday following the end of the survey week, which includes the 12th of the month, so is sometimes pushed back by the calendar.

Photo credit, Elkhart Indiana, a bellwether of manufacturing activity, in the rain. Philippa Dunne

Eagles, Eels, and Forever Chemicals

Wildlife ranges are forever changing. As is becoming more widely understood, species most now migrate to find appropriate new habitats in our changing world, not just to find food and shelter as the seasons change. These days, with the climate changing more quickly than species are able to migrate, they need our support through scientifically planned wildlife corridors, overpasses, and breeding refuges.

Citizen scientists have long assisted in tracking changes in migration patterns and ranges, a crucial role as field science is notoriously under-valued and underfunded. If you ever see a truly distinctive bird, like a swallow-tailed kite, out of its usual range, you need to discipline yourself to trust your eyes, even if your bird book suggests the bird is 1,000 miles too far to the north. In the old days you then had to search around for print reports confirming such sightings, but now we have eBird.org, a wonderful example of how citizen scientists can support conservationists. In recent years black vultures, glossy ibises, and Mississippi kites have all extended their breeding ranges far northward, and eBird has been tracking their progress. A vibrant roseate spoonbill showed up in New York last week—its official range extends from South American into the coastal waters along the Gulf of Mexico.

eBird also tracks dramatic cases that excite some birders eager to see a distant species, and trouble others because a vagrant of a vulnerable species is clearly lost. In August of 2020, a Steller’s Sea Eagle showed up near Alaska’s Denali Park. A bird presumed to be the same eagle was spotted in March of 2021 along Route 59 in Goliad, Texas, perhaps blown off course by a winter storm. In December the eagle again believed to be the same (we have to keep saying that because we don’t actually know) was seen around Taunton, Massachusetts, before passing through Nova Scotia, and landing in Maine in early 2022. Sightings a few weeks ago put it in Spaniard’s Bay in Eastern Newfoundland. The usual range of this vagrant runs from Korea up through the Kamchatka Peninsula, home to a large breeding population. Sometimes the raptors, with a wing span of 8 feet, show up in the Aleutian Islands and even Juneau, but this trip is clearly stunning.

The Texas sighting included a photograph—there is close to zero chance such a sighting would get past the eBird.org proctors without digital evidence—and to confirm the accuracy, a team from the Texas Bird Records Committee went out into the field and found the exact post where the eagle had perched. One birder reported that the unexpected appearance of hundreds of birders at a working wharf in Maine could have caused an ugly scene, but instead the mood was “bemused, pleasant, and happy.” Although these days science often drives a wedge between us, that’s an example of how it can bring us together.

Citizen scientists can also take a lead in the health of their own communities. Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory introduced such a project in one of their ongoing Science Cafés, informal open-floor events intended to advance ground-breaking biomedical research.

Jane Disney who, among other things, oversees the Community Environmental Health Laboratory at MDI labs, has been working with hundreds of citizen scientists testing for toxins like arsenic, a crew that has now turned their sights to PFAS as well. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances, PFAS, are manufactured chemicals used to make products water- and oil-repellent. But they also contain carbon-fluoride bonds that do not break down naturally, hence the moniker “forever chemicals,” and have been linked to many serious diseases generally associated with aging. In 2021 Maine’s Department of Environmental Protection released a list of priority towns where contamination is linked to the use of sludge, septic-tank sewage, and industrial waste as fertilizer, often on dairy farms. To give you an idea of the complexity of the work, the DEP staff compiled lists of sites they suspected had received 10,000 cubic yards of sludge that was likely contaminated with PFAS, in small rural communities in both Aroostook and Waldo counties, and in cities like Lewiston. These all fall within a half-mile of people’s homes and include a dairy farm where PFAS levels in milk were 150 times the state standard, with some sites perhaps cross-contaminated.

Dr. Disney is working with local homeowners who do find PFAS in their wells to come up with a strategy. Here the divide between wealthy and poor communities is pretty stark. Filtration systems are beyond the reach of some households, and concerns about PFAS are coming up “a lot” in discussions with the residents. A poorly maintained filtration system can be worse than no system, and one participant made the point that since people who rely on municipal water supplies are guaranteed water free of dangerous pollutants, provisions should be made for those without access to such commodities who rely on their own resources. Some scientists are working on ways to break down those carbon-fluoride bonds, but citizens need protections now.

Fred Bever, the Chief Communications Officer at MDI, and he really is an excellent communicator, invited everyone to the upcoming Science Café, the Science of Beer, that will be held at Fogtown Brewing in Ellsworth. If you’re in the region, be there or be square.

Birds, bright and beautiful as they are, tend to get more attention than other species critical to our habitats, like small solitary pollinators, and grubby bugs. A species that really needs our help is the American eel, a critically endangered creature whose life cycle remains an ongoing mystery. Homer’s mentions “eels and fish” in the Iliad, which caused ancient Homeric scholars to question the passage, noting that Homer would surely have known eels are in fact fish. Aristotle was puzzled by their life cycle, and even young Sigmund Freud tried to figure out how they reproduce.

Their spawning grounds in the Sargasso Sea weren’t discovered until 1920, and even now no one has seen an eel breed. Damming of rivers, over-fishing, and pollution have devastated eel populations. In 2003, Bob Schmidt, a founding biologist Hudsonia, an ecological research firm in the Hudson Valley, set up nets at the mouth of the Sawkill on the Hudson River to track their population levels. (If you are in the area, please get in touch with Philippa if you want to join us on the water next spring. Your fingers and toes get cold, but on sunny days the elvers shimmer as they briefly pass through your hands.)

Newly born elvers are transparent, making it hard for fish finning beneath them to see them, and soon after birth drift up from the Sargasso on the currents, a voyage that takes a year. Upon reaching our tributaries, they begin the next stage of their lives, swimming up over waterfalls and human structures, getting further and further inland as, in the words of one researcher, they become larger and more experienced at negotiating the waters. After twenty or so years they swim back to the Sargasso, now they are dark above and white below, camouflaged against both predatory birds and fish, to breed and die.

Science communities are international, and it’s pretty certain that the many individuals contributing to these efforts do not vote along the same party lines. We’ve highlighted research in the past underscoring the importance of volunteer work and social interaction to ameliorate the isolation and depression so often in the headlines these days. Nature provides us with everything we need to stay alive for free. In the three instances outlined above, cooperation not only benefits those working together, it improves the chances that the natural world can continue to labor on our behalf.

Philippa Dunne & Doug Henwood

Photograph: Passamaquoddy Indian Township Reservation