Inside Voices: A Look at Clinician-Experienced Racism

This is something new for us. We hear a lot of stories, many relating experiences outside our own that open doors to broader understanding of the many lives that make up the American experience. Today’s author, Fatima Adamu-Good, is an occupational therapist and writer with 15+ years of experience in research, diversity advocacy, urban design, quantitative analysis and cultural competency. As an advocate for diversity, equity and inclusion, she has collaborated with local and national leaders in the healthcare and non-profit communities to address systemic racism in clinical practice, delivered presentations on the detrimental effects of implicit bias in the academic sphere and published articles highlighting the experiences of people of color as they strive for success. She is currently an adjunct professor in occupational therapy at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Fatima told us this story in passing, and was kind enough to write it up. Thanks also to Stephanie MacKay for edits.

A Look at Clinician-Experienced Racism

One morning in early April of 2020, an occupational therapist walked toward the room of the newest rehabilitation patient at a skilled nursing facility in Southeastern Pennsylvania. She mentally reviewed information from the patient’s hospital chart*; race: White, gender: male, age: late 70s, weight: 185, height: 5’ 9”, past medical history: unremarkable, the reason for admission: fall with hip fracture and subsequent replacement. The therapist grabbed a rolling walker conveniently located next to the doorway, prepared for a standard intake process; this was the latest fall/hip fracture patient in a line of the many seen in a facility devoted to geriatrics. Upon entry, the patient seemed fatigued but well-oriented to his surroundings. He peered skeptically from smeared glasses and said, “Whoa! What’s going on with that hair?!”. The therapist, taken aback, reached up to touch her afro, styled the same way it was every day. The next morning, her supervisor informed her that the patient had requested non-African-American rehabilitative and nursing staff because he “had difficulty understanding the instructions” of African-American staff.

That therapist was me.

What are the economic consequences of the above anecdote? There is a financial cost to attitudes and policies colored by racism as the 2020 Peterson and Mann report on the economic impact of inequality makes clear. African-Americans currently make up 12.8% of the country’s population and the cost of their exclusion from higher education access equates to $90-$113 billion from 2000 to 2020. Such encounters as the one I experienced undermine remedial initiatives that increase the quality of care for African-American patients. The percentage of African-American physicians is currently 5%, less than half the overall population share. The avoidance of preventive care services accounts for 75 percent of national healthcare expenditure and reduces economic output by $260 billion a year. Efforts to increase national figures for African-American doctors, such as the $100 million contribution to historically black medical colleges by former New York Mayor Michael Bloomberg, could also reduce economic opportunity barriers while buoying GDP.

A 2020 cross-sectional survey in the Journal of Family Medicine found that twenty-three percent of the 71 physician participants reported a patient directly refusing their care due to race. It concluded that physicians of color experienced significant racism while providing health care in their workplace and were likely to feel unsupported by their institutions in which they practiced. Another study, in 2007, of minority medical students, showed a correlation of racial bias with burnout and depression symptoms in 48% of participants. Before its 2008 apology, the American Medical Association failed to address 100 years of the racial inequalities African-American physicians faced, and excluded them from vital organizational conversations. African-Americans are underrepresented amongst the management that determines patient-handling policy, the business people who fund these measures, and the professional staff that control who enters educational institutions and higher-wage occupations. The aforementioned structural imbalances need to be remedied to ensure that income gains fostered by the growing share of African-Americans physicians, and the companion better health outcomes for their patients, are not eclipsed by sidelining and burnout.

The CDC reports that deaths from the Sars Cov-2 virus in racial minority groups are more than 50% higher than in White or Asian persons residing in the United States. This surge in deaths has a resonance with another set of findings with economic roots and ramifications for an entire demographic category. The 2015 Case and Deaton paper chronicling a marked increase in mortality for middle-aged non-Hispanic White working-class people identified educational attainment, access to mental health services, and availability of stable work as life and death determinants. Louisiana, one of the ten U.S states with the highest African American population, demonstrates a microcosm of a larger pandemic pattern: African American Covid19-positive patients had a higher prevalence of conditions manageable via preventative healthcare services such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and chronic kidney disease. These patients were also three times more likely to have Medicaid insurance than white non-Hispanic patients. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) has made a dent in the country’s uninsured numbers and could be critical in addressing inequities in care-access; between 2013 and 2016, the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid lowered the uninsured rate for non-elderly African Americans from 18.9 percent to 11.7 percent.

In other, heartening, news, there has been a marked increase in African-American applicants to medical schools since the Covid-19 pandemic began. If the face of healthcare is more representative of the communities most in need, it equates to increased traffic through a clinic’s halls and consequently an increase in revenue along with quality care. Many potential African-American patients avoid utilizing preventative care services for fear of discriminatory treatment. A Stanford study reported higher communication levels between African-American male patients and doctors of similar ethnicity, extrapolating conclusions to indicate better cardiovascular health outcomes for such patients by 19%.

When an incident of overt or covert racial bias against a clinician does occur, current institutional methods of redress are lacking.

Any ameliorative strategies to address the racial inequalities created in our centuries-old simmer, fueled by bias and frustration and detailed in this research note are rendered toothless if framed as ethical issues or limited to philanthropic gestures. Much of the literature reviewed for this article framed the racially biased patient phenomenon as an ethical dilemma, left to be either addressed or more often ignored by White senior physicians, clinicians, or administrative staff. Targeted and purposeful investment is critical in order to achieve the best economic outcomes framed by years of research that repeatedly concludes that income inequality and race have wide macroeconomic consequences. The Covid19 pandemic has made it clear that all these factors are intimately intertwined. Now’s our chance to restructure a society-wide foundation offering broader economic opportunity while building resiliency and better health outcomes for those who have been excluded and underrepresented.

The scope of the pandemic-related public health crisis has brought many societal inequities into stark relief, none more glaring than the impact of racial disparities on physical and economic health. I have experienced the drain that racism has on institutional resources and the quality of healthcare first-hand. My supervisor chose to reassign the White male patient to the caseload of a less-credentialed therapist simply because they were White and not because they were more qualified to treat him. As a daughter of Nigerian-American parents, I was taught to excel at everything I do, for better or worse. Can you imagine the sense of betrayal at the realization that my good faith efforts to learn these valuable skills, years spent hunched over textbooks working six and seven days a week to pay for graduate school, were put in jeopardy by racism?

A 2016 survey of 400 White medical students and residents found that 50% believed that African Americans felt less pain due to thicker skin. I sometimes wonder if patients, colleagues, or superiors presume the same about me, that I am impervious to physical, psychological, and emotional pain. I do not have thicker skin, but I am angry and weary of institutional injustice that disproportionately hurts so many, which this pandemic can no longer let us deny. Feel my anger, know my anger, respect my anger. And join me, even in the smallest of gestures, to collectively channel that anger towards meaningful change. I am hopeful that more of the collective will begin to understand that to hinder one is to hinder us all.

Further reading/References:

https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/other/surge-in-african-american-medical-school-applicants-drive-to-action-by-covid/vi-BB1dslXB

https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/03/graying-america.html

Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. https://www.nejm.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMsa2011686

https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/figure-18-percentage-all-active-physicians-race/ethnicity-2018

Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. http://pnas.org/content/113/16/4296.abstract

Does diversity matter for health? Experimental evidence from Oakland. https://siepr.stanford.edu/research/publications/does-diversity-matter-health-experimental-evidence-oakland

Williams, D. R., & Rucker, T. D. (2000). Understanding and addressing racial disparities in health care. Health care financing review, 21(4), 75–90.

www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/white-health.htm

https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=61

https://www.census.gov/popclock/

https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/413324

https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat11.htm

https://www.cdc.gov/404.html

https://journals.stfm.org/familymedicine/2020/april/serafini-2019-0305

https://www.cdc.gov/404.html

www.statista.com/statistics/200970/percentage-of-americans-without-health-insurance-by-race-ethnicity/

“…because they are beautiful to themselves.”

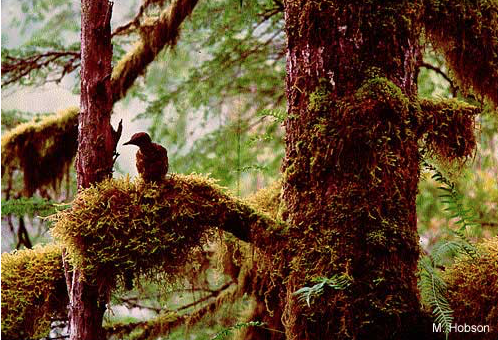

As our many different springs draw migratory birds to the northern hemisphere, it’s a nice time to think about the contributions women have made to the field of ornithology. For example, Eleanor’s falcon, the slender long-distance migrant that stuffs dragonflies into its mouth while flying, and wings across the Sahara when travelling between the Mediterranean and Madagascar each year, is named after Eleanor of Arborea (1347 to 1404) As one of Sardinia’s most important judges, Juighissa Eleanor included protections of raptors’ nests when she enacted the Carta de Logu, Sardinia’s legal code in place from 1395 to 1827. As you can probably guess, those protections were among the first that we know of. (The Carta also gave daughters and sons equal inheritance rights, among many important things, but not for here.)

Charles Darwin wrote to a friend in 1860 that “the sight of a feather in a peacock’s tail, whenever I gaze upon it, makes me sick,” apparently because he didn’t understand the utility of male adornment. Long observed that male birds sing longer and more complicated songs than females, Darwin later came up with the idea of sexual selection–the more complicated the song, and the snazzier the get-up, the more irresistible to choosy females. Arguing that females are “too amused by passing fancies” to have any evolutionary sway, Darwin’s Victorian colleagues attacked his thinking for giving females control. One argued that peacock plumes came from “a surplus of strength, vitality, and growth power.” In order words, Darwin’s colleagues were cute when they were mad.

A big controversial topic still. Yale ornithologist Richard Prum recently argued that beauty is the driving force behind extravagant plumage, animals are “agents of their own evolution,” and “birds are beautiful because they are beautiful to themselves.”

But getting back on topic, regional differences in bird song have led to bias toward documenting the predominantly male voices of the temperate regions where, to protect territory and attract females, male’s songs have become “more elaborate over evolutionary time.” As ornithology became more gender balanced, female ornithologists broadened the geographical range of song study to Australasia, where song birds are believed to have originated. They found many singing females, some singing to protect territories alongside males throughout the year. The old question–why do only males sing? –has been replaced by an effort to understand why in many migratory species the females have severely cut back or dropped their songs.

Additionally, University of Northern Colorado’s Lauryn Benedict and Cornell’s Karan Odom have documented far more female bird songs in the northern hemisphere than most understand, including duets with males, and other forms of communication.

So, take Dr. Odom’s advice, and don’t assume every bird you hear singing is a male. There are even conservation consequences—it you think all singing birds are males, you’ll put together some mighty challenged habitat maps.

You can give Drs. Odom and Benedict’s team a hand by reporting instances of singing females you observe here, and please note the international effort, emblematic of science.