New Trends: Education and Party in Michigan

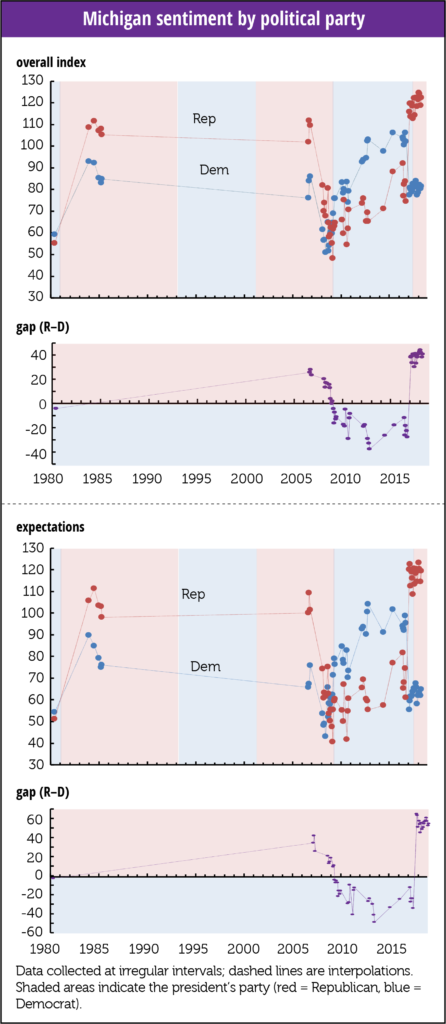

First, party: The University of Michigan collects data by political party only sporadically, so we don’t have a full history but, as we brought up at the time, last May, Richard Curtin, the guy who puts it all together, noted that in fifty years, the survey had never recorded as “dominant a political effect,” as it did in early 2017. Curtin expected that divergence to converge, but instead it widened.

Here’s the graph we ran:

During the years Trump has been President, Republican sentiment has averaged 117.6; while that of Democrats averaged 80, meaning Republican sentiment is running 46 points above the Obama years, while sentiment among Democrats is running just 13 points below. Both calculations exclude the depth of the recession years, when the divergence straitened to just 9 points; whoever thought we’d remember anything reassuring about those years.

That effect continues. In an October presentation Dr. Curtin identified his “major underlying issue,” as whether economic expectations surveys can retain their predictive ability given their “responsiveness to political rather than economic developments.” He quotes some observers who believe the partisan effect is “uniquely tied to the Trump administrations,” but his research suggests it is tied to our old friends income inequality and wage stagnation.

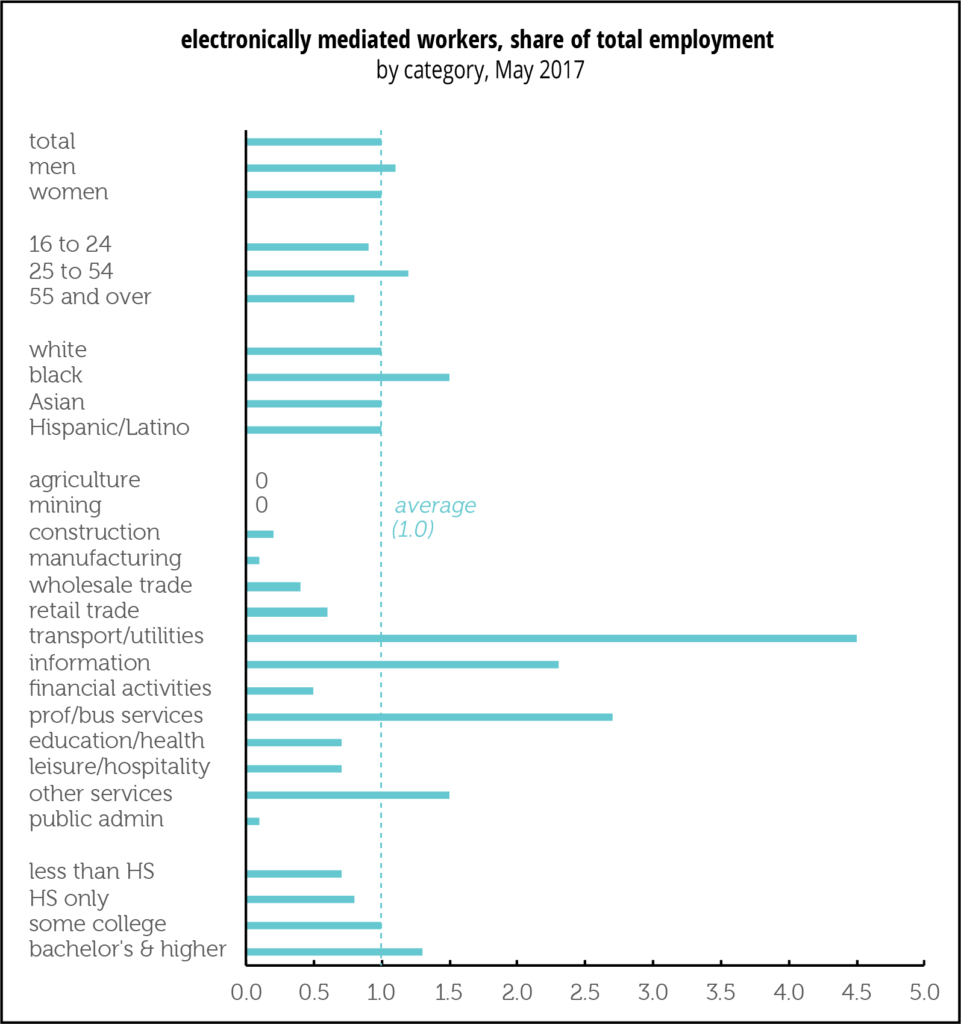

Second, educational attainment: Curtin also revisited the fact that the partisan divide between those with college-degrees remains “very low and insignificant,” and built on the striking observation he made back in May: the demographics really changed in 2017. Through 2016, generally, assessments of economic possibilities rose with income and education, and fell with age.

That changed in 2017.

Overall expectations for those with less than a high school degree had risen from 68 in October 2016 to 82 by August 2017, but fell for those with a college degree from 87 to 80. For those 65+ they rose from 2016’s 69 to 83 in 2017, while slipping a bit, to 86, for those 18 to 34 years old.

May 14, 2018

Sentiment for all three education terciles tracked each other closely throughout the series, all peaking around 2000, high school at 100 and the two college groups at 120, before falling raggedly to about 60 in the recession. The current divergence is led by an increase in the outlooks of the two lower attainment levels while those with a college degree are basically flat.

Curtin suggests that those with “relatively low job skills, as proxied by education, were the most affected by Trump’s election.” As we mentioned when we first brought this up, it’s a good thing if people with lower skills can do better.

But it’s a very bad thing if partisanship is putting a dent in the value of formerly trusted economic data.