Productivity: The Gruesome Details

Productivity is one of our obsessions, and it should be a national obsession as well.* Clearly it isn’t. The industry statistics presented here show that for a lot of industries, the last couple of years have been a real bust.

The stats, provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, cover scores of industries, with the manufacturing sub-sectors particularly finely broken down. Here we’ve provided what is fashionably described in some circles as a “curated” list of industries, since the whole set is beyond our scope.

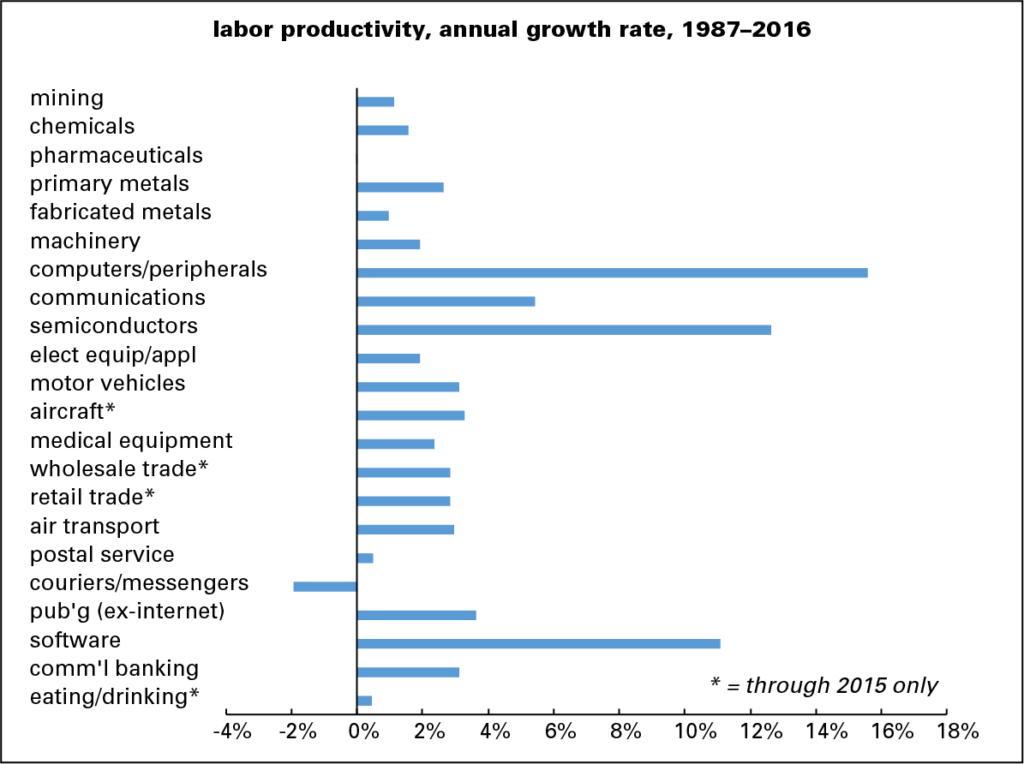

First the long sweep, from 1987 (when this series begins) through 2016, graphed below. (The 2016 data isn’t available for all industries; those for which 2015 is the terminal year are marked with an asterisk in all three graphs.) The standouts are, not surprisingly, in high-tech: computers, semiconductors, and software, all with annual gains in the double digits. Some old-line industries, like motor vehicles, aircraft, and wholesale and retail trade, turned in solid performances.

Eating and drinking establishments and, perhaps surprisingly, pharmaceuticals did quite poorly, with pharma slightly in the red—an amazing, if invisible on the graph, feat for such a technology-rich enterprise. And perhaps even more surprisingly, the postal service did better than private couriers and messengers, where productivity declined over the almost three-decade interval.

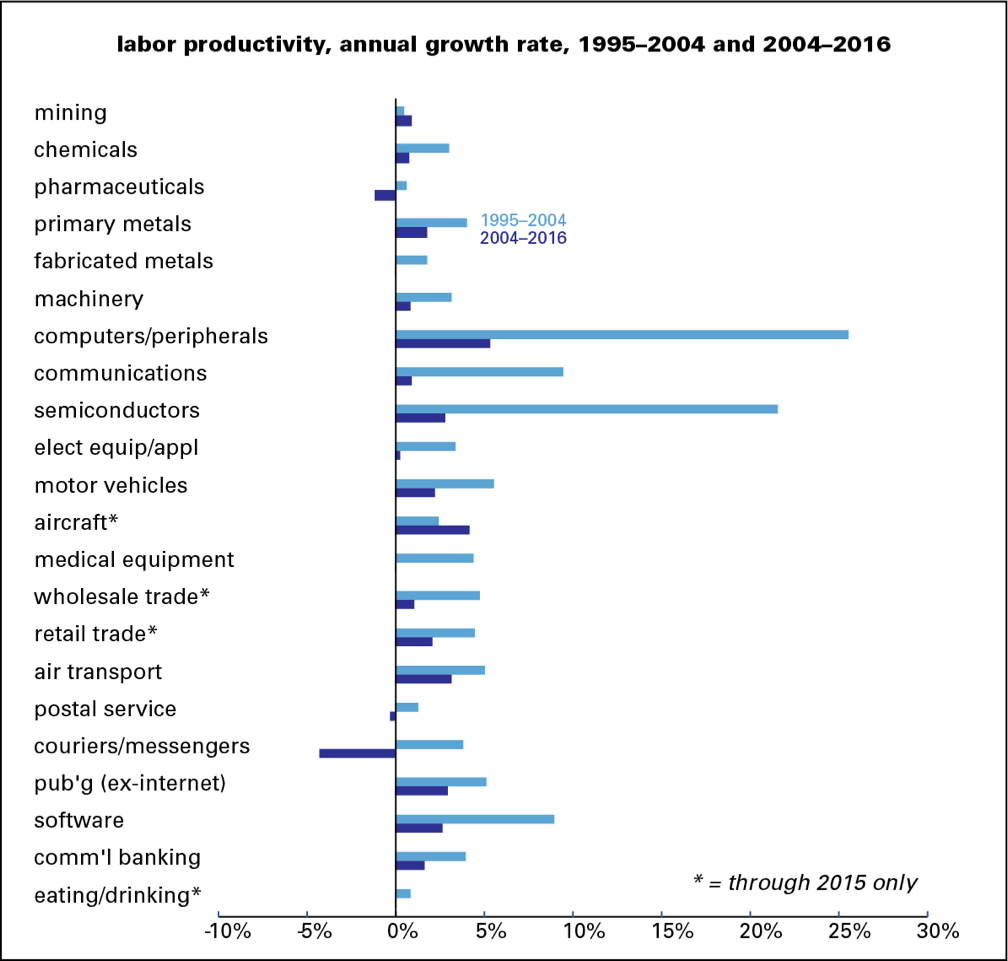

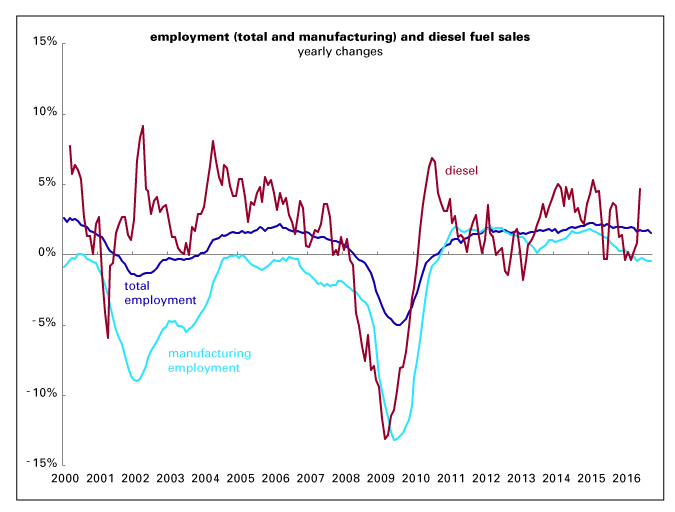

But as the graph below shows, most of the stellar performances were logged during the productivity acceleration of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Of the 22 industries shown, 20 saw a decline between that period and the last twelve years—a decline of over 4 percentage points on average. Only mining and aircraft showed a pickup. Computers and semiconductors fell by around 20 percentage points. Pharmaceuticals went from positive to negative.

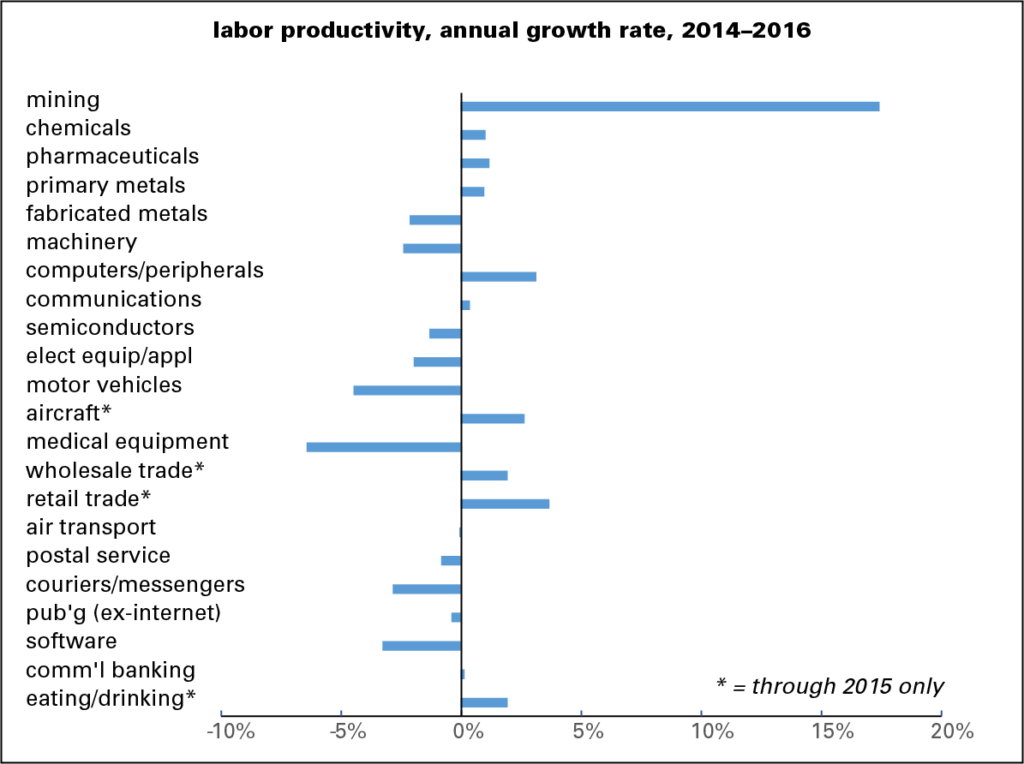

And the last couple of years have been fairly terrible. Half the industries showed a decline in productivity. Only mining—fracking, one assumes—had a strong performance. Computers remained in the black, but semiconductors fell below zero. Motor vehicles and medical equipment were firmly negative.

The productivity slowdown that we’ve been following at a high level is a pervasive problem at the industry level.

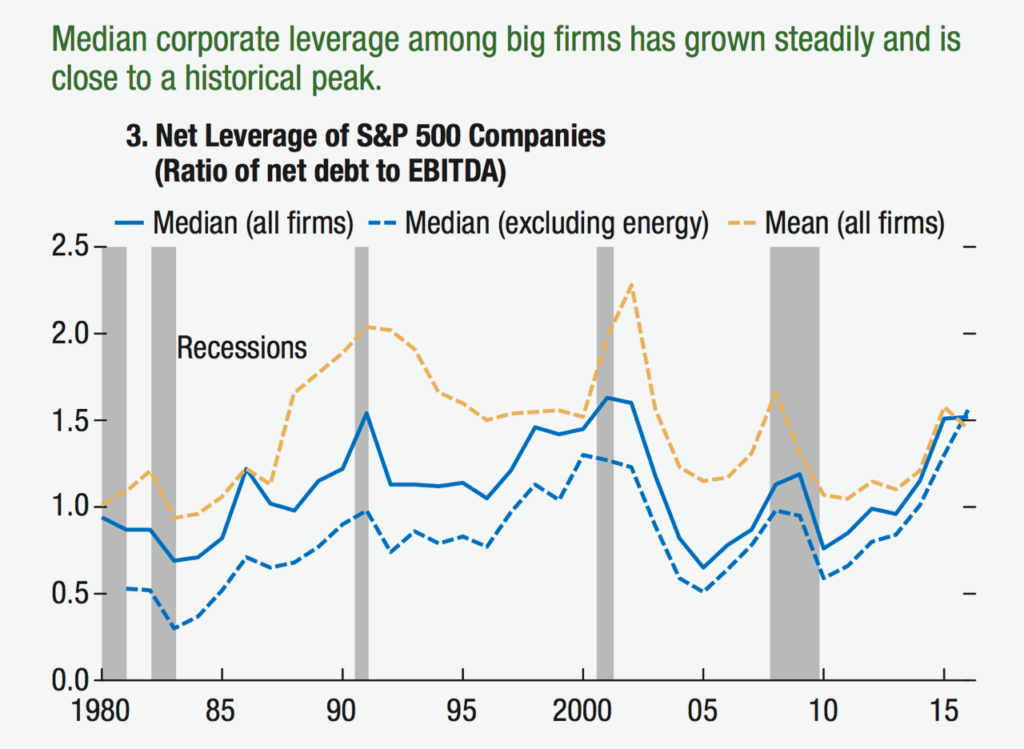

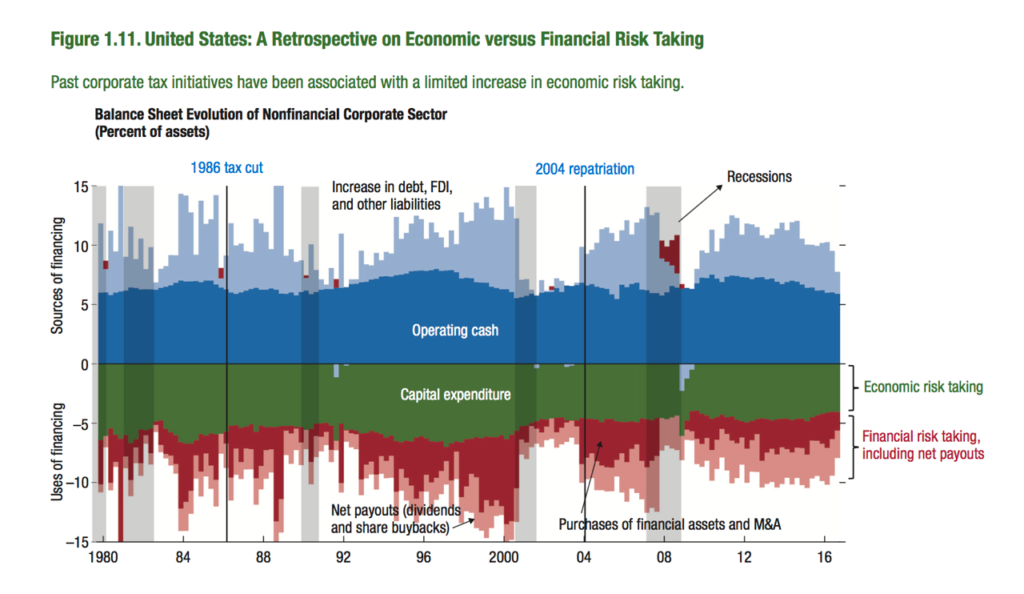

* For those of you not so obsessed, productivity determines our standard of living. An increase in productivity means greater output from the same input, which makes labor more valuable, which in turn lifts wages. Too many corporations are currently using their profits, and money borrowed on the cheap, to buy back their own stock and pay dividends to their investors instead of investing in productivity enhancing research & development, and physical capital. That’s one of the big factors in sluggish wage growth.

All This, and Indentured Servitude Too

It’s no secret that many of our more vulnerable workers have it tough these days.

In July, the Treasury Department decided to take a look at the widespread use of non-competition agreements among low-wage workers as a factor in ongoing low job churn and wage growth.

Additionally, Case Western law professor Ayesha B. Hardaway is looking into the proliferation of these “non-competes” among low-wage low-skill workers as a condition of their at-will employment as a violation of the 13th Amendment. She argues that Reconstruction Era debates, legislation passed after the amendment itself, and judicial opinions of the time make it clear that the prohibitions against indentured servitude and peonage in the broader amendment were intended to prevent wage slavery.

Which is what you get if you put at-will employees on this particular one- way street. They are not protected by contracts and, since they cannot seek like similar employment elsewhere, have no bargaining power.

And therefore no economic mobility. Hardaway argues that such use is outside the original scope of post-employment restrictive covenants, which were designed to protect trade secrets, thereby encouraging employers to invest in new ideas and in the training of their employees.

Restrictive employment covenants have been addressed by the courts for centuries, and US legal thought on such matters came, originally, from British courts in the 16th century. These courts generally put attempts to restrict work opportunities of former apprentices under the rubric “improper and unethical motives of masters.” Specifically, applying the rule of reason, the court stamped the idea that an apprentice could not seek employment in the “very trade he honed during his apprenticeship to be morally improper and outside ordinary norms.” Such thinking on employment restrictions held in England, although specific confidentiality clauses, and non-solicitation and non-poaching agreements, Hardaway’s “original scope,” generally got the green light.

And so it was in America until the late nineteenth century, when judicial decisions began to wear away the precedent set by the test of reason. Even so, through the twentieth century such agreements were limited by the courts to high-level employees with access to proprietary information, employees whose names and reputations themselves often added value to the company. These sophisticated workers are on a two-way street: at the same time they sign such agreements, they also sign employment contracts.

Hardaway believes that subjecting low-wage un-skilled workers to similar arrangements “fails to comport with the established rule of reason.” Indeed, and worth thinking about with the Politics of Rage getting so much ink these days.