Non-Productive Poaching: It’s a Thing

Hat tip to Josh Lehner, of the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, for suggesting we look at The Dual Beveridge Curve by Anton Cheremukhin and Paulina Restrepo-Echavarría, of the Dallas and St Louis Feds.

We’re outlining their research here, and strongly recommend you look at the graphs if you don’t have time to read through the paper. We were planning to take up a few other papers on the Great 3-Rs Debate—Resignation, Retirement and now Renegotiation—in this issue, but we’ll leave that for later to focus on this paper. It presents a very different way of considering the Beveridge Curve. To us it’s a real relief to have creative researchers getting into this instead of shrugging it off as a mystery, or building inaccurate narratives.

Some ads are looking for workers from the pool of the unemployed, others aim to poach employees. The two objectives target different skill sets, and have different effects on the labor market: a job shift has no effect on un- and employment rates, but a hire from the pool of unemployed workers does.

When the authors first call their view “extreme,” we thought, hey, it actually could just as easily be called highly logical. The extreme comes in because their “simple” model breaks the overall search and matching process into two non-overlapping processes: the two sets work in “separate, segmented” markets.

This departs from the usual practice that aggregates all workers, the employed and the unemployed, who may be searching for a job, with all vacancies, adds something new to the literature, and also contributes to the measurement of the searches of the employed.

In their underlying remarks they note that 99% of the unemployed spend some time actively looking for work, which is in line with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ definition of being unemployed and with survey results, but that a far smaller share of the employed search for work. Using the Survey of Consumer Expectations and work by Jason Faberman they put that at about 22%. The employed are more efficient than the unemployed at finding work.

In their words, a “proper” Beveridge Curve should only include ads aimed at the unemployed. To do this, they break the Beveridge Curve out by sector, creating adjusted curves, which take the mystery out of the curve’s behavior. If you exclude the poaching ads, you end up with a very ordinary curve. (Please note they used the Household Survey adjusted to be like the Payroll Survey for this, not that other noisy thing.)

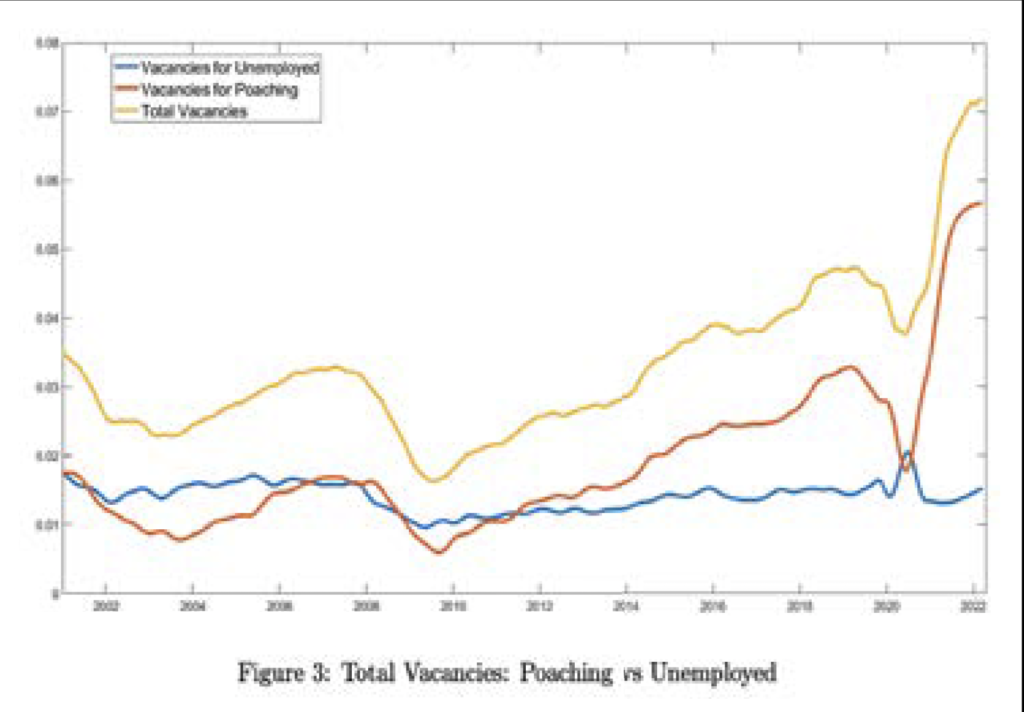

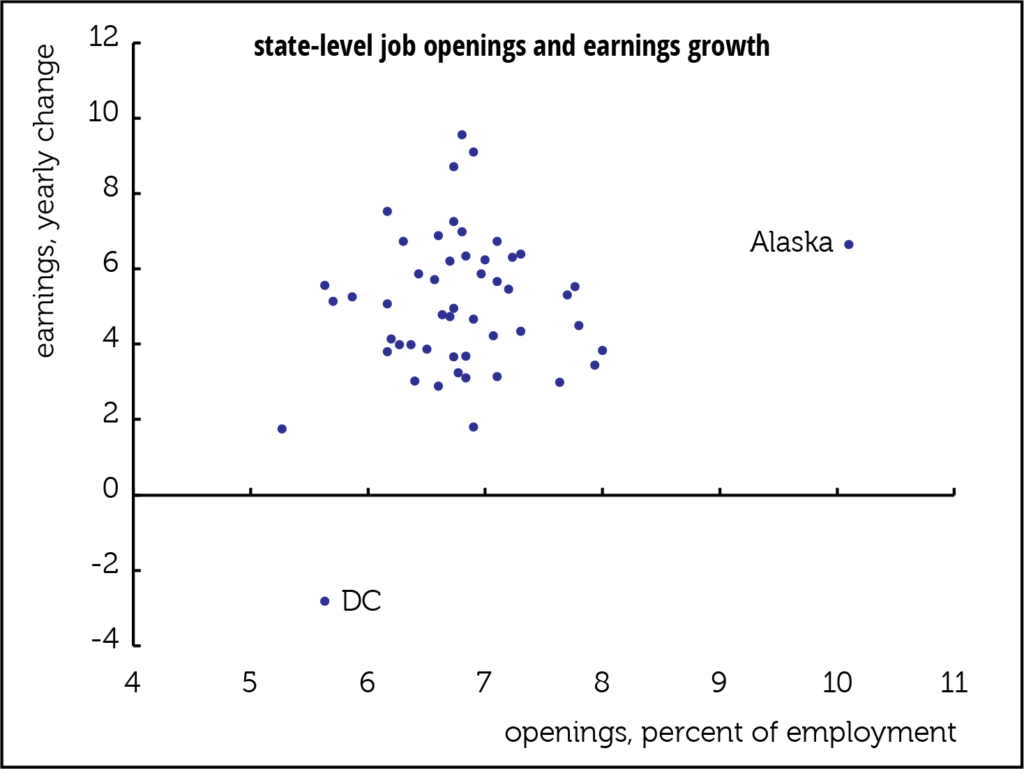

We snapped their graph (below), and you can see that the increase in poaching ads increased significantly in 2015. In their words, the curve shifted up at that time because of “a dramatic increase in non-productive poaching vacancies.” (We’ll say dramatic. That graph is as stunning as the openings rate was unbelievable to us.)

There was some drama in the most recent recession. Poaching vacancies dropped in 2020 and quickly recovered, but vacancies fishing for the unemployed rose in the recession, a time of social distancing, high unemployment, and decreased poaching. Spurred by measures to control the pandemic, more workers were laid off than could be explained by the fall in demand, and many were hired back quickly.

At this point, fiscal and monetary policy drove up demand, firms needed to expand, and that poaching reaccelerated. Supply bottlenecks and demand led to a surge in goods inflation, and poaching drove up wages. That’s what happened recently, and Cheremukhin and Restrepo-Echavarría are searching micro data to understand what drove the poaching surge in 2015.

Considering what will happen to unemployment, they note that in the 2000s ads designed to poach and those designed to draw were about the same, but now the majority of job openings target the employed. That would suggest the decline in openings might have an historically small effect on unemployment, and here they mention a soft landing.

But they add a caution. If mismeasurement is improving, then the Beveridge curve has shifted outwards, but the slope has not changed, and we don’t have the steepened curve required for the soft landing. Then a decrease in vacancies could drive an increase in the unemployment rate.

They also reference work done in 2013 showing that as of 2011, 42% of hires came from firms that did not report any openings. Alas, wider knowledge of that study might have saved us a lot of time spent squabbling over the openings rate.

Coda: Back in 2015, just as the yet-to-be-explained surge in poaching got underway we renamed, and in print, the openings rate the “Tire Kicker Rate,” on the belief that employers were just fishing, and raised many red flags that the openings rate was not doing well as an indicator, and it was likely driving faulty policy.

And that’s the sobering fact in this paper: The narrative was that unemployed workers were either too unskilled or too lazy to work. All the hullabaloo about job openings and the unemployed was misdirected. The companies were angling for workers already employed elsewhere, and the unemployed took the rap.

NCAs: Theory, meet data

Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan has an opinion piece in the New York Times covering the FTC’s proposal to forbid the use of noncompete agreements (NCAs). We want to highlight new research presented in one of the papers she cites, “The Labor Market Effects of Legal Restrictions on Worker Mobility,” by Duke’s Matthew Johnson, Ohio State’s Kurt Lavetti, and Michael Lipsitz of the FTC. The paper makes many points, and references work on the rise of superstar firms, on domestic outsourcing, and on the weakening of unions as possible pressures causing the “downward acceleration” of labor’s share of income. Then they present their new work on gauging the effects of levels of NCA enforcement.

On the bright side, NCA could increase firms’ investment in training, knowledge that might increase workers’ productivity and earnings, but research suggests a darker pattern of depressed earnings instead. When we have written about NCAs pressure on wages and start-up formation in the past, some readers have suggested they are not a problem as they are not enforced. That is true, however, research suggests they are nonetheless threatening to workers who may not understand that, especially low-wage workers with lower educational attainment.

There are also cases of lawsuits involving stiff fines for low-wage violators, and the use of NCAs is growing. A recent study found that somewhere between 28 and 47% of private-sector workers are subject to NCAs. The authors referenced a 2014 “high-quality” study that put the share at 18%, noting the disparity may be explained by the passage of time.

Understanding how NCAs affect labor markets has proved “elusive,” and lack of comprehensive panel data has limited research on enforceability, leaving other potential but unobserved causes lurking. Johnson, Lavetti, and Lipsitz’s paper constructs a new panel that employs “within state changes” to isolate the effects of enforceability. They make the interesting point that the “vast majority” of changes in enforceability law come through judicial decisions, and suggest that’s a consequence of the importance of precedent in law in the courts. To them, judges are “more constrained than legislators in allowing economic or political trends to affect decisions.” They, tactfully, point out that was helpful in the design of their research.

Their research found that although, in their estimates, about 17% to 47% of the workforce is bound by NCAs, the effects extend beyond those workers. Negative externalities on wages including reduction of labor market churn, thinning labor markets, and higher recruitment costs. In studying markets that cross a state border, they found changes in enforceability in one state affected workers in the adjoining state. They cite the large body of literature showing that employed workers’ wages rise when their outside options improve, and that wages are more closely aligned with the minimum unemployment rate over the course of one’s job spell than to the rate when the spell began. Although they find this holds true on average, in states employing strictly enforceable NCAs the minimum unemployment rate has “essentially no effect” on the workers’ current wages, while the rate at the beginning of employment has a much stronger effect. In states with low enforceability, the effect of the longer run unemployment rate is “even more pronounced,” the start rate less.

They show NCAs extend inequality. Women are less likely to violate terms of their NCAs and more hesitate to commute, and strict enforceability reduces earnings of non-white and female workers by twice the reduction of white male workers’ wages.

They conclude that strict enforcement of NCAs ”fundamentally changes” wage negotiations, moving them from a model of implicit contracts and costless mobility, to one of implicit contracts and costly mobility. They find that by shutting down on-the-job wage growth, enforced NCAs deprive workers of a primary way to increase their incomes. By regressing the labor share of income at the state level using NCA enforceability, they find a jump from the 10th to the 90th enforcement percentile is associated with a 2.3pp decline in labor’s share of income. And that 2.3pp difference is about one-third of labor share’s decline over the last 80 years.

The FTA proposed rule is up for public comment, and Khan invites us, especially those directly involved, to weigh in to make sure their work is based in reality, not theory.

There is a lot of scholarship on this topic. Chair Khan doesn’t mention the link to former slave-holders following the Civil War—a tie shared with tipped employment—but that work is available two-clicks into the footnotes. Ayesha Bell Hardaway’s Paradox of the Right to Contract is a classic.

Instead dismissing NCAs because they are often not enforced, it might be more useful to wonder how our society came to tolerate repurposing a covenant designed to protect intellectual property to preventing a minimum wage worker from seeking higher wages at a different establishment. The personal damage caused by NCAs falls disproportionately on minorities and women, but the overall damage to productivity, new business formation, disruption and innovation, affects us all.

Philippa Dunne & Doug Henwood