In a new piece of the wage and job-churn puzzle, the Treasury Department recently published a report on the widespread use of non-competition agreements around the country.

Non-competition agreements, which surely our readers are familiar with (!), are intended to encourage businesses to invest in their workers by reducing the likelihood that the worker will move elsewhere, and to encourage inovation by protecting trade secrets, a trickier argument to make since such secrets are often protected by other law.

The Treasury Department, however, is looking into detrimental effects on worker mobility, and hence wage growth, innovation, and new business formation. Although media headlines glommed onto doggie day care workers laboring under such agreements (which is either laughable or outrageous, take your pick), the Treasury lists fast-food employees, warehouse workers, and camp counselors as other signers, and wonders where the social value lies in asking an entry-level low-wage burger flipper to sign a two-year non-compete. There is a lot of important stuff in the Treasury and other reports tied to free markets, innovation and “perfect information,” all crucial aspects of a vibrant economy but perhaps currently straitened by onerous legalities.

It’s a complicated subject: not all states enforce such agreements, some are overly broad and hence get thrown out of court, in some states employers can revise agreements after the fact to make them enforceable, in others they can’t. One study found that, as of 2015, non-competes were enforceable in about half of the states even in cases where the employee was fired without cause. Some researchers speculate these agreements allow companies to hire, preferentially, workers with a lower propensity to depart, especially since such workers could not convincingly make that case on their own, except by a willingness to accept such a restriction, which would be less of a burden to them. On and on.

Understanding has a big role in this as well. Many workers—and we’ve heard this from some high-level strategists in the financial sector—don’t fully understand what they are signing, and the preferential hiring argument rests on just such an understanding, probably a weak link. For example, California has among the highest percentages, 22%, of such contracts, but noncompetes are generally not enforced at the state level there, so employers are relying on workers’ lack of knowledge about the legal system.

On to a barrage of percentages: Nationally, 19% of our workers are currently restricted by such agreements, and close to 40% have signed them in their working lives.

Although there are questions about the overall benefits even for math and computer specialists, such limitations make the most sense in such fields and, indeed, about one-third of high-tech and math workers have signed non-competes. On the other end of the spectrum, about 14% of workers who are either making less than $40,000 a year, and/or do not have college educations are also clenched by such agreements.

Ten percent of workers reported bargaining on their non-competes, and 38% of the non-bargainers did not know they could do such a thing. In many cases such agreements are proffered after the employee has accepted the position, as in turned down all other offers. Treasury estimates that the lower bound on this after-the-acceptance practice—a new use for a tired term—is 37%. In one study 70% of highly skilled electrical workers were asked to sign such agreements after they had accepted offers, half of the time after the first day of work, another affront to perfect knowledge. The Treasury report points out that this kind of tactic need not be used if the agreements truly were beneficial to both parties.

Only 24% of all workers report having trade secrets in their possession, and these workers, as well as those who interact with clients, are understandably more likely to have signed non-competes. But less than half of all workers who have signed noncompetes meet these standards, which “suggests” to the Treasury that protecting trade-secrets “does not explain the majority of these contracts.”

And related litigation is on the rise: A 2013 study commissioned by the Wall Street Journal showed either a rise in the prevalence of non-competes, or perhaps a “significant” increase in their enforcement, and law firm Beck Reed Ridden ferreted out a 61% increase in the number of employees getting sued under these agreements between 2003 and 2013.

On the legislative side, recently Oregon limited such agreements to 18 months, and Hawaii prohibited them for all tech workers, which Missouri legislators proposed but were unable to pass. Maryland and New Jersey are working to make non-competes unenforceable if a worker is eligible for unemployment insurance benefits, with Massachusetts, Michigan and Washington proposing to make them generally unenforceable. Proposals in Minnesota and Connecticut would bar such agreements for workers making less than $15.00 an hour, while Georgia recently amended its constitution, no less, to allow for greater enforcement.

How goes it around the world?

Law protecting free trade generally makes such agreements unenforceable in India. In the UK an employer must demonstrate what is being protected; “competition”itself doesn’t make the grade. Many countries impose more limited tenure on such agreements, and many require those sidelined to be paid a portion of their former salary, a quarter in Romania, a third in France, and half in Germany and Belgian, for example.

Why does this matter?

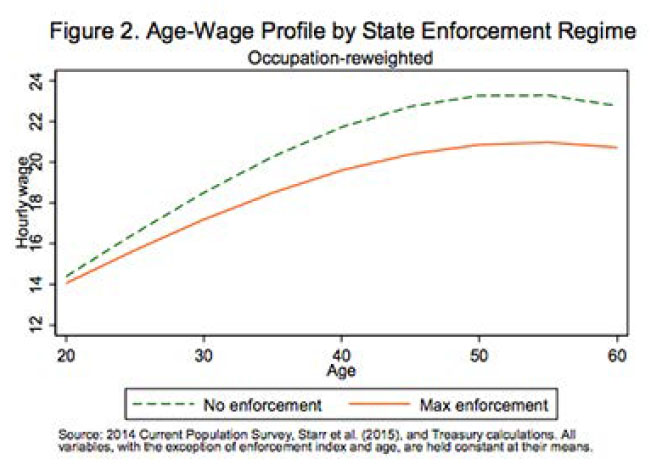

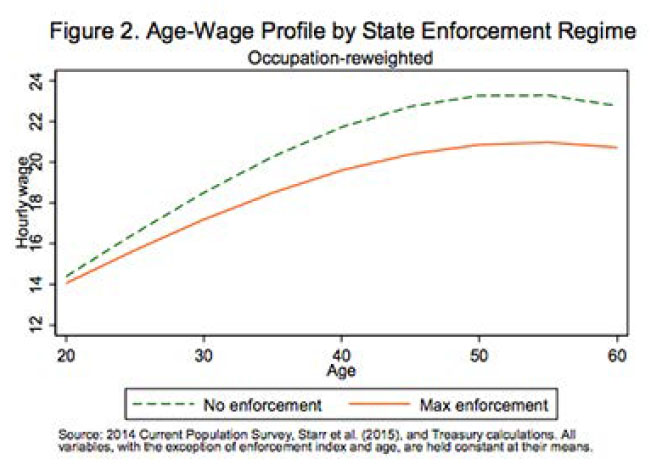

Wages: Non-competes erode bargaining power, and have an adverse effect on wage growth. We grabbed the graph below from the Treasury piece comparing wages, reweighted by occupation, in states with heavy and no enforcement.

Of course, it’s not a slam-dunk: Median household incomes in California rank third in the nation, and are about 150% of 33rd ranked Georgia’s median household incomes. Clearly there is more at play there than California’s lack of enforcement and Georgia’s more aggressive stance.

Innovation and productivity: We know that high-tech firms often cluster in regions with competitive suppliers, large numbers of qualified workers, and “information spillovers” among firms. Of course, such spillovers are not always beneficial to firms whose ideas are on the move, although they will rotate into the taking position again. But spillover is one of the drivers of innovation, job churn and productivity and so is beneficial to regional economies on the whole.

Some studies referenced within the Treasury piece note that workers tend to migrate to states were enforcement is weakest, hence contributing to brain drain of specific regions.

In their paper “Do strict trade secret and non-competition laws obstruct innovation?” (not free online) two specialists, Charles T. Graves and James A. DiBoise argue that, whatever we have come to believe about protecting intellectual property, the real innovators are the creative job-hopping employees themselves, and anything that restricts their mobility impedes the advancement of valuable “destructive” technologies. They suggest reform would be a good thing, and they have something to lose in suggesting this: they both represent employees in noncompete litigation.

Harvard law professor William W. Fisher working with Felix Oberholzer-Ghee of the Business School in their paper on developing an integrated approach to managing intellectual property make the point that although intellectual property rights represent a “significant fraction” of enterprise value, recent surveys show that less than half of current business leaders understand how important such rights are, or are actively involved in strategic planning. They note that IP management is handed off to legal departments who are little involved in strategic planning, and strategic managers don’t work together.

This double-silo approach leads to short-sighted solutions, most lamentably legally driven attempts to leverage their IP possibilities in a way that derail important network effects, and “worse yet, enable competitors to capitalize on network effects.”

We often argue that R&D spending is below where it should be. Efforts to control employee movement read as a dinosaur in the vibrant high-tech world, and such squabbling suggests too much attention to the fencing, and not enough to the care of the herd.

We’ll end with this wise advice from the irascible HR Examiner:: “Your Trade Secrets are Secret For About 27 Days. Or 27 minutes. Really, the secret way of doing almost anything is over… Why are you focused on the rear-view mirror and trying to protect something that will be obsolete long before the lawsuit is over?”

Coffee into the Waves

For us, a good remedy for the brutal political tenor in the country these days is to read long and hard. You always figure that someone like Stuart Hampshire, who during his high-school years in the 1930s watched the men unemployed by the closing of the Mersey shipyards stamping their cold feet in the streets of Liverpool, while the women sold wildflowers to passers-by. He saw kids without shoes while shoe factories were laying off workers because they couldn’t sell their shoes, and coffee jettisoned into the sea for price controls. He knew those shipbuilders could well remain unemployed unless or until the looming war ramped up demand for ships. When that war did so he went into intelligence work focusing on the espionage efforts of Himmler’s Central Command, and came to believe there is nothing we are not capable of doing, and that a “thin layer of procedural justice” is crucial in balancing competing moralities within a society. He calls such justice more important to morality than courage (we’ll add that’s “acting from the heart”) because, say, a bookish life might require little courage. “Not so for justice, always required.”

Hard to argue with him, and he does a far better job of incorporating Shakespeare throughout his books than we ever have.

But we bring Hampshire up because he makes the distinction between restrictive morality, what we must not do, and the immorality that results from a lack of imagination. It’s not being Pollyannaish to say that the posturing that has replaced insight and discussion as we confront the economic issues we face these days has led to a profound failure of imagination, to all of our peril. And all the while the combatants fiendishly defend their negatives, what they believe cannot work.

Oh, and, Hampshire calls, “Which side are you on?” a “fatally over-simple question.”