Our Take on January Jobs

This was basically a solid report, with job growth above recent averages. (Part of that strength was good business practice, and part of it technical, more below.) Wage growth strengthened, but hours were surprisingly weak.

Employers added 200,000 jobs in January, 196,000 of them in the private sector. Both are about 20,000 above the average of the previous six months. Goods production extended its strength, with mining and logging up 6,000 (just above its average over the last year); construction, 36,000 (firmly above average); and manufacturing, 15,000 (slightly below average, with the plus signs concentrated in durables). Private services added 139,000, just above average, with wholesale trade up 10,000 (well above average); retail, 15,000 (quite a contrast with its average of -3,000, with most of the gain coming from clothing stores); transportation and warehousing, 11,000 (just below average); finance, 9,000 (also just below average); professional and business services, 23,000 (more than a third below average, with accounting/bookkeeping in the red for the second consecutive month, and temp firms unusually weak); education and health, 38,000 (just below average, though health care alone was almost a fifth below average); leisure and hospitality, 35,000 (above average); and other services, 6,000 (a third below average). In the red: information, off 6,000, twice its average decline. Government added 4,000, most of it federal, as losses in state gov were offset by gains in local.

As we mentioned in yesterday’s report, seasonal factors anticipated heavy lay-offs in construction and retail work. Surely construction businesses are holding onto their workers in the current environment; those are real jobs, if somewhat enhanced by the factor. The strength in retail, though, was probably driven by weak hiring in December, which caused the factor to over-adjust for anticipated January layoffs.

For the year ending in January, total employment was up 1.5%, and private employment, 1.7%. Both are down 0.2 point from where they were in January 2017 – and both those 2017 numbers were also down 0.2 from January 2016. And the 2016 numbers were down 0.3 (total) and 0.4 (private) from January 2015. Claims that employment growth over the last year have been extraordinary are overdone; the cycle’s peak employment momentum was February 2015’s 2.3%, almost three years ago.

Diffusion indexes were surprisingly weak, with all four intervals down. We wouldn’t make much of this now, but it bears watching.

The average workweek fell 0.2 to 34.3 hours. Declines of 0.2 in the hours series are rare: there have only been seven declines of 0.2 or more (six -0.2s, one -0.3) in since the all-worker series began in March 2006. We’ve seen several instances of 34.3-hour workweeks over the last couple of years, but it is the low end of the range since hours climbed out of the recessionary basement in late 2011. Both manufacturing and services were down.

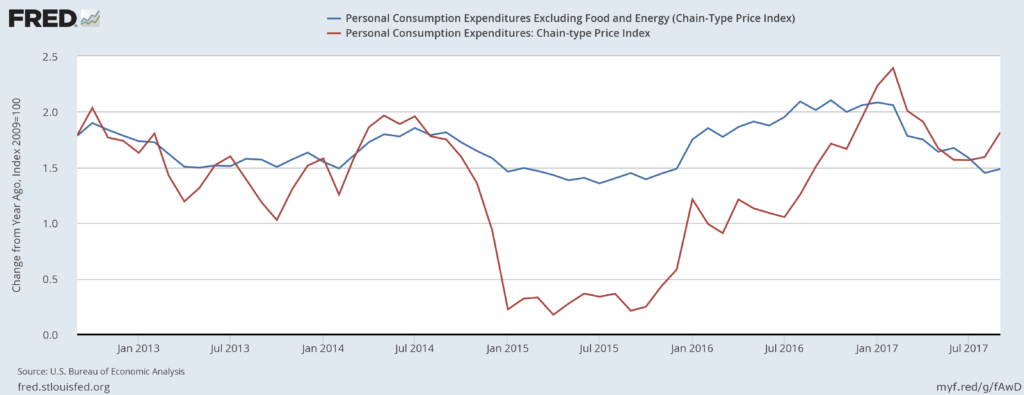

Average hourly earnings rose 0.3%, taking the three-month moving average up from 0.2% to 0.3%. (We confirmed with the BLS that they have corrected a timing issue affecting wages, so no more fun with that flaw.) The annual gain is now 2.9%, and has risen 0.2pps in each of the last three months. In 2016 the gain for all workers was 2.5%, and in 2017 it was 2.4%. Oddly, you have to go back to June 2009 to see wage growth of 2.9%.

Production and non-supervisory workers’ wages were weaker at 2.4% over the year. We reverse engineered supervisory workers’ wage gains using their share of the workforce, graphed above. You’re see wages for supervisory workers are currently growing at 3.9%. A year ago wages of production workers were growing at 2.3%, while wages for supervisory workers were growing at 2.6%.

Because of the sharp decline in the workweek, aggregate payrolls – hours times earnings times employment – were off 0.1%, the first decline since March 2017.

The benchmark revision announced by the BLS last fall was put in place, once again a non-event. Total employment as of March 2017 was lifted 0.1%, which is below the 0.2% absolute average of the last 10 years. That average has fallen, by the way, which means the monthly estimates have been more accurate in recent years. Over the last five years the revisions were absolute 0.1%. with one too small to count.

This month brought the annual changes to the population controls for the household survey, which makes most month-to-month comparisons non-kosher. The BLS did provide information on several measures adjusted for the changes in the population controls, and those developments were not lapel-grabbing: the participation rate, the employment/population ratio, and the unemployment rate were all unchanged before the changes in the controls, as they were after. And total employment, up 409,000 as published, would have been up just 91,000 were it not for changes to the population controls. The changes increased the size of the noninstitutional population by 488,000, the labor force by 333,000, and employment by 318,000 – not large numbers in the long view, but large enough to muddle comparisons with December.

The unemployment rate has been 4.1% for four consecutive months now. While some analysts are calling for a move towards 3.5%, this stability is starting to look late-cycle-ish.

Weather effects were strictly average for a January.

Because of the changes to the population controls, there is nothing that can be reliably said about the duration of unemployment or the job flows numbers.

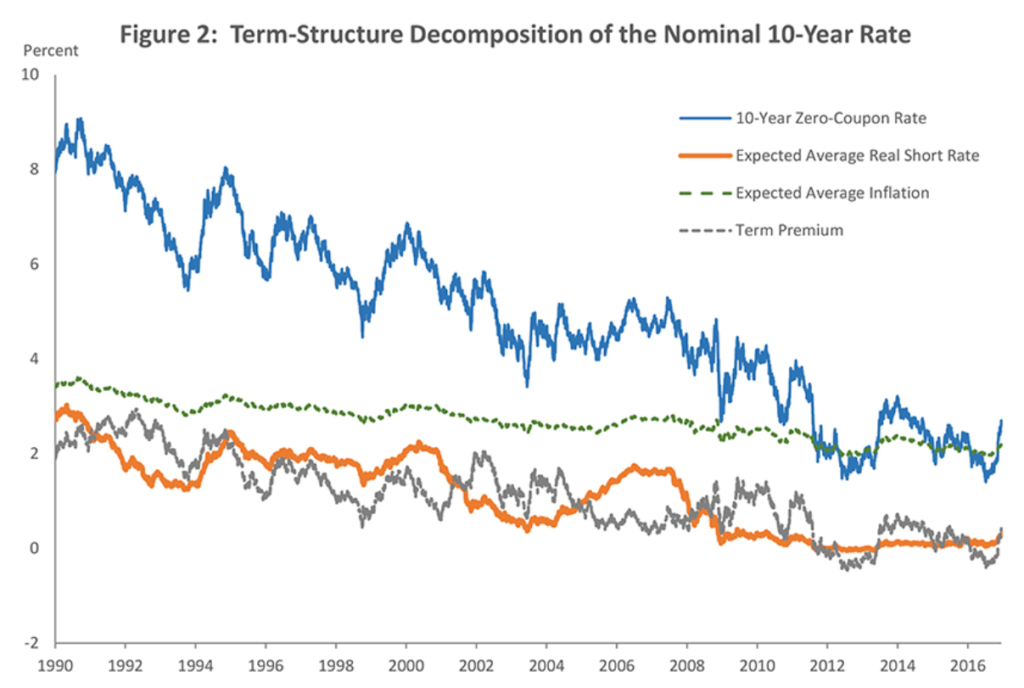

The above-consensus rise in employment and strengthening wage growth will bolster the case for further rate rises. It will be interesting to see how dependent on low rates the financial markets and corporate cash flows have become; preliminary signs from stocks suggest there will be some adjustments coming in 2018.

Richard Yamarone

Many of you already have the heart-breaking news that the wonderful Richard Yamarone stopped breathing yesterday afternoon; he had a heart attack on Thursday morning while playing hockey with his team, his Thanksgiving tradition.

In 2009, Captain Chesley Sullenberger safely landed his crippled plane on the Hudson River. So accomplished was he that he planned to hit the river where he thought there would be no boats, telling passengers to, “Prepare for a hard landing.” I remember thinking at the time it would have been admirable if the monetary officials could have been so blunt in 2007.

Rich was. Back in the early days of the recovery he wrote, “The recent depression—ask any real economist.” He never confused the height of the markets with the state of the economy. He thought about workers and wages, inequities, rigged systems, and he worked incredibly hard. He was incisive, deep, an awesome singer, and truly hilarious. His humor made it easier to take some of his darker observations. Once he was outlining a dreadful eventuality when suddenly he noted it was odd that we were both laughing. (I’ll leave it to those in his league to cover his fly-fishing abilities.)

A tremendous man, a tremendous friend, and a tremendous economist, the real kind.

And he had a burly Welsh heart. Also a pilot, Rich too would have thought about the boats on the river.

Rich was 55.

In today’s note his closest friend Dave Rosenberg wrote that Rich “managed to squeeze many lives into one short one.” Josh Frankel added a lovely image, his idea for a Bloomberg late night show called “Yammy in his Jammies,” featuring Rich running down, say, the nonfarm payrolls in feety pajamas. Dean Eisen called him open and honest about himself—simple words but hard to do. Josh Rosner, “He measured others, generously, by the kindness in their hearts, but few could have truly been measured against his own.” (More here.)

And don’t miss him singing and playing.

We loved Richard.

Last night I dreamed that a mighty redwood fell in the forest.

Philippa