Coal Country, Shadblow, and Spring

We’ve written about the sophistication and inclusion of coal-mining communities in their early days, of land theft, empty promises, and hopes that were revised away. In a new NBER working paper, Canary in the Coal Decline, Josh Blonz, Brigitte Roth Tran, and Erin E. Troland—the first and last of the Federal Reserve, the second of the San Francisco Fed—report on the broad effects of the decline in coal mining on household finances in Appalachia. Removing coal from our energy mix is a top priority if we want to clean up our energy act; everything about it is enormously filthy, from mining it to burning it. But what are the human costs of the transition away from it?

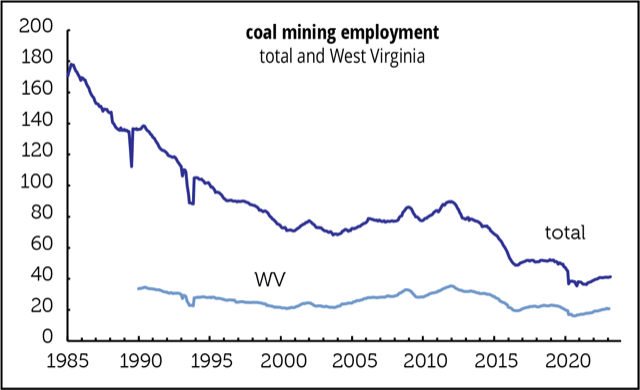

To answer those questions, the authors use data from the New York Fed/Equifax panel, which is the same source as the New York Fed uses in its consumer credit series. They look at important measures of household economic well-being between 2011 and 2018—a period when total employment in the industry fell by 43% as total employment rose 11%—in counties with a heavy concentration of coal mining. Here’s a long-term look at coal employment:

Coal-rich Appalachia has long been one of the poorest parts of the country, with relatively low educational attainment by national standards, a gap that has been widening. A good bit of the reason for this is that coal has been in decline for far longer than the last decade or two—it’s more like a century. Coal has become progressively less competitive economically compared to natural gas, as both plant construction and extraction costs have fallen (thanks to fracking, which won’t win any environmental awards either).

Even though coal accounted directly for only 2% of employment in what they define as active coal-mining counties, the economic impact of the decline was much broader and more severe than that small share would suggest. For example:

• Credit scores in coal-intensive regions were about 3 points lower than they would have been otherwise. That may not sound like much, but other researchers have found that even a 1-point decline can be economically meaningful. The effects went well beyond the 40,000 miners who lost jobs nationally over that seven-year period (three-quarter of them in this survey area). The effects were concentrated among those in the bottom half of the credit-score distribution. At the 40th percentile, roughly at the cutoff for subprime classification, the credit score hit was 7 points.

• Those credit score declines translated into a 50-basis point increase in mortgage interest rates.

• Declines in coal demand resulted in increases in the share of households ranked as subprime, more intensive use of credit cards, higher delinquencies and collection rates, and more entries into bankruptcy.

• Damage was felt most in the second-lowest quartile of credit scores—in other words, people were on the verge of falling into serious hardship. But even those in the top quartile take a hit—a small one, but evidently no one is safe from the contraction in coal country.

• None of these findings are driven by age.

As the authors note in their conclusion, these finding are a warning about what might happen in other fossil fuel producing communities as carbon-based energy sources recede in importance. They don’t note, but we will, that the political effects of this impoverishment can be harsh, underscoring the need to insulate affected regions against the harms coming from an essential energy transition.

Case study

A footnote to the above: a closer look at the state most closely identified with coal (both by outsiders and residents), West Virginia.

Having such a coal-centric economy has not been kind to the state. West Virginia has the second-lowest employment/population ratio (EPOP) in the country, 52.6%, just behind South Carolina and above dead-last Mississippi. That’s 7.6 points below the national average and 15.2 points below the leader, Nebraska. Even at the peak in the national EPOP, 64.7% in April 2000, it was turning in a miserable 52.8%.

West Virginia has the fifth-highest poverty rate, 15.0%, 3.8 points above the national average and nearly three times the state with the lowest rate, New Hampshire, 5.6%. Coal made a lot of people rich over the decades—just not ordinary West Virginians.

That’s why transformative work being done by outfits like the Ohio River Valley Institute is so important, as are targeted programs like the Hickman Holler Appalachian Relief Scholarship, founded by musicians Senora May and her husband Tyler Childers, to provide scholarships to regional schools like Morehead State University. MSU is known for its STEM programs, and HHARS is giving priority to African-American students. Regional farmers’ markets too.

Philippa Dunne & Doug Henwood

Shadblow, one of many popular names for Amelanchier, was once one of the first trees to bloom in the Appalachian spring.

Long Violent History

The pensive face of young Tyler Childers is popping up on computer screens around the world. The son of a surface coalminer, this Kentucky singer & songwriter’s first release was “Bottles and Bibles.” and he is known as the spokesman for the people in his region who often struggle financially. In his statement about his new song, Long Violent History, he simply asks his community to put themselves in the shoes of African-Americans who fear everyday encounters with “public servants,” the police. In the song itself, he wonders how many “boys could be pulled off this mountain,” before his community swarmed into town, demanding “answers and armed to the teeth.”

One of his ex-fans suggests his expression of these “liberal views,” which include not getting shot in one’s sleep, have ended his career, a bit of a stretcher since his new page had over 50,000 likes within days of posting. In the accompanying song, the weaponry he describes includes Pawpaw’s old rifle and Springfield 30-06s. You may know what an aught 6 is but I (that’s Philippa) had to look it up, a rifle introduced in WWI, largely retired but still in use as a regular old hunting rifle. And the uprising he invokes is the Battle of Blair Mountain, a bona fide labor struggle over conditions in coal mines, not some ridiculous gun rally or ghastly display or racism or anti-Semitism. I hope you will take the time to listen to his statement. It’s a marvel.

His solution is to vote out those who have let police brutality run, and he suspects that these same people are the ones who hollowed out his and like communities–jobs out, drugs in–in what have become food deserts. He encourages his community to spend more time growing food, canning, hunting, fishing, and tanning hides, so they don’t have so much time to jawbone about things they know nothing about.

Good advice for everyone, and we know Tyler Childers wouldn’t be such a fool as to go deer hunting with an AK-whatever.

All proceeds from the song go to the Hickman Holler Appalachian Relief Fund that he set up with his wife, Senora May, a beautiful story all her own. They are in the process of setting up a scholarship fund to support people of color attending Appalachian colleges.