Here we revisit a familiar topic: the decline in the labor share of national income. We were prompted to revisit by a recent post to the St. Louis Fed’s website with the provocative title “Capital’s gain is lately labour’s loss” (Anglo spelling in original). It draws on the work of Loukas Karabarbounis and Brent Neiman (KN), which we’ve also discussed, though mostly in passing. KN’s data runs only through 2012; the St. Louis Fed post draws on their in-house FRED database to update it through 2017 for five major economies.

The declining labor share is interesting for several reasons. For decades, most economists assumed the share to be constant, which makes it far easier to develop economic models of production functions and economic dynamics. But the labor share is not constant. In their examination of 59 countries with at least 15 years of data between 1975 and 2012, BN found 42 with a declining labor share, measured against corporate value-added. A major reason is the declining cost of investment goods; the St Louis researchers present a series showing a near-relentless decline in the price of capital goods vs. consumer goods since 1948, with an acceleration in the 1980s. (The average decline from 1948 through 1979 was 1.6%; from 1980 to 2016, 2.6%.) That makes it easy to substitute capital for labor, to the detriment of labor’s share.

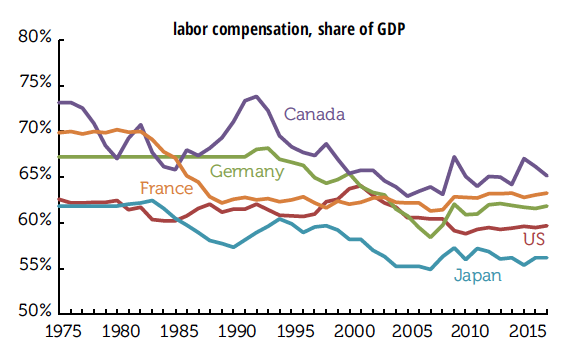

The extension of the data for the five years doesn’t change the fundamental story. The labor share in the five economies shown in the graph on the top of p. 7 was little changed between 2012 and 2017, despite sharp declines in the unemployment rates in most. You might think that a tightening labor market might boost labor’s share, but that hasn’t happened.

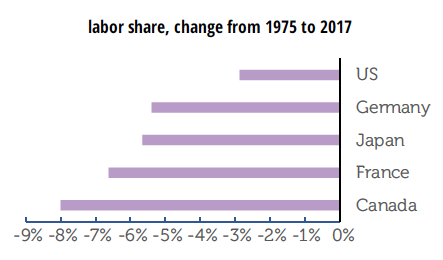

As the graphs above show, the declines happened to different degrees and over different intervals for the five countries shown. The declines range from 3 percentage points in the US to 8 in Canada; expressed as percentage (not point) declines, they range from 5% in the US to 11% in Canada (with the other four countries not far behind). Remember, it had been a well-established axiom in economics that this was not supposed to happen.

BN find that most of the decline in the labor share has happened within industries, so it can’t be explained by compositional changes such as the shift from manufacturing to services, which, among other things suggests things other than globalization are at work (given the varying exposure of different industries to international competition). And they also find a decline in the labor share within China, which makes it an unlikely culprit for the decline in the labor share in the richer countries.

They conclude that the decline in the price of investment goods accounts for about half the decline in labor’s share. An interesting question is what accounts for the other half. They don’t examine the effect of labor market deregulation and the declining power of unions, but those seem like worthy avenues of investigation, as they have been in other research pieces.