For better or worse, Congressional Budget Office (CBO) is the the go-to authority on budget projections. They are planning to update to their economic and budget projections in a couple of weeks, and we thought it would be interesting to look back on some of the CBO’s past projections. The results of that exercise make us want to say “for better or worse indeed.” And one more endorsement of the CBO official who expressed his opinion in 2007 that forecasting out more than a year or two is a waste of taxpayers’ money.

Just as we write when we’ve review the Fed’s economic projections, we don’t want to make fun of them: economic forecasting is a treacherous business. No doubt prudence demands that what is sometimes called “the forecasting community” give it the old college try, but one should regard the results with considerable skepticism.

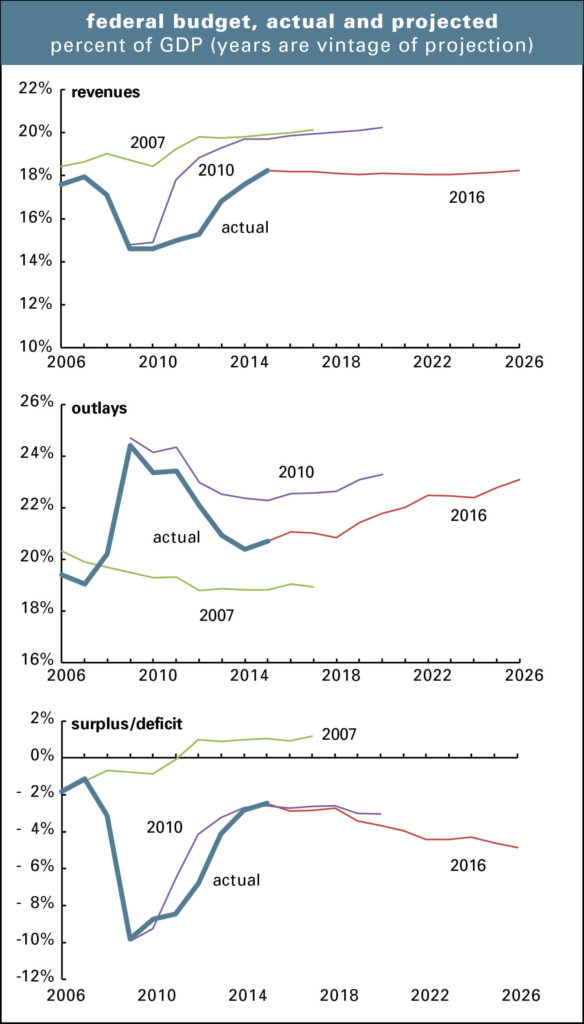

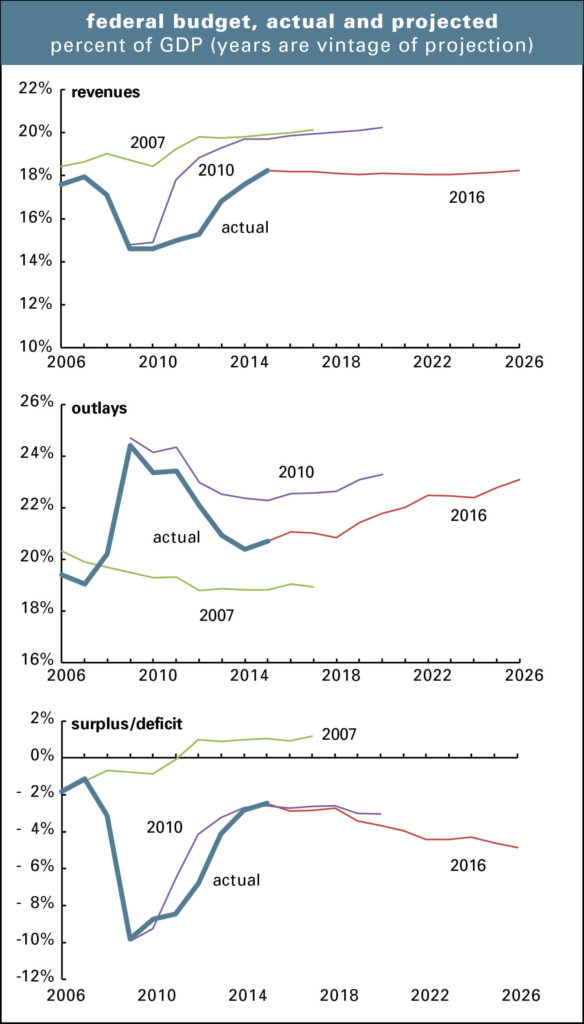

The graph below shows several vintages of CBO ten-year projections for the major federal budget components compared with the actual history. We chose January 2007, because it was about a year ahead of the business cycle peak; January 2010, because that’s when we were crawling out of the Great Recession; and March 2016, because that’s the most recent exercise. The CBO was wildly optimistic about revenues in 2007, and surprisingly so again in 2010. It’s now projecting revenues will be essentially flat as a share of GDP for the next ten years. Given the trajectory of the “actual” line, that flatness seems unlikely, though of course that was an unusually volatile period.

The outlay projections are also quite off-target—way too low in 2007, and way too high in 2010, almost as if the stimulus program would go on forever. The CBO is now forecasting a sustained rise of about 3 percentage points of GDP in outlays over the next decade—but the 2026 endpoint is below where it thought the 2020 level would be in 2010. And all are above the neighborhood it was thinking about in 2007.

As for the number the bond market is most interested in, the deficit, those projections aren’t so great either. For some reason, in 2007, the CBO thought the budget would soon be running in the black; it projected a surplus of 1.0% of GDP in 2012 compared with an actual deficit of 6.8%. It got the direction of change basically right in 2010 (despite having gotten the revenue and outlay projections rather badly wrong), though it got a little ahead of what reality would turn out to be. It’s now forecasting a gradual increase in the deficit over the next ten years. That is the standard wisdom, but given this track record, should we believe it?

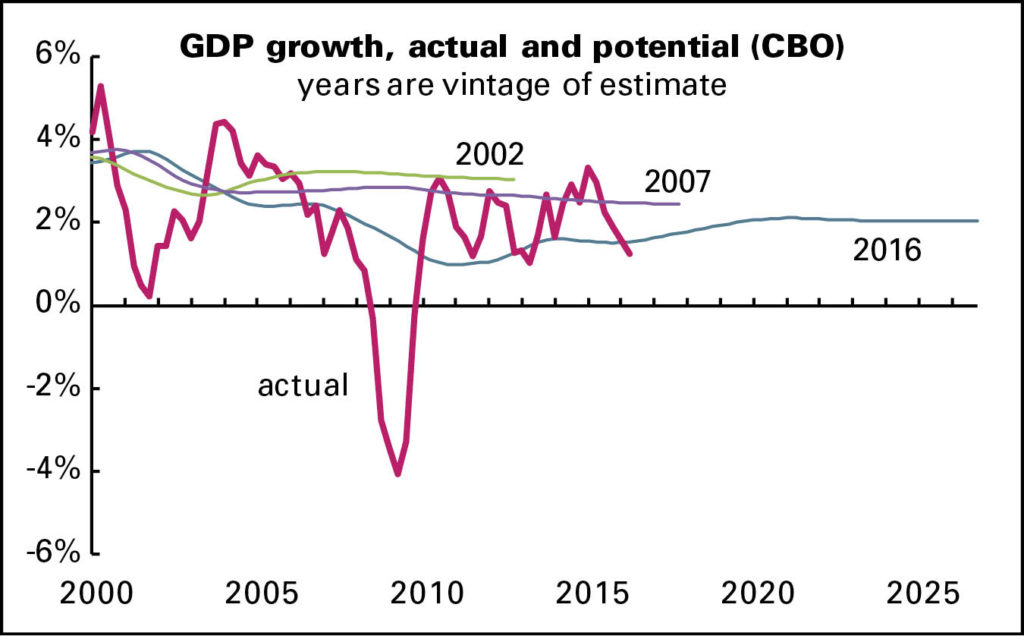

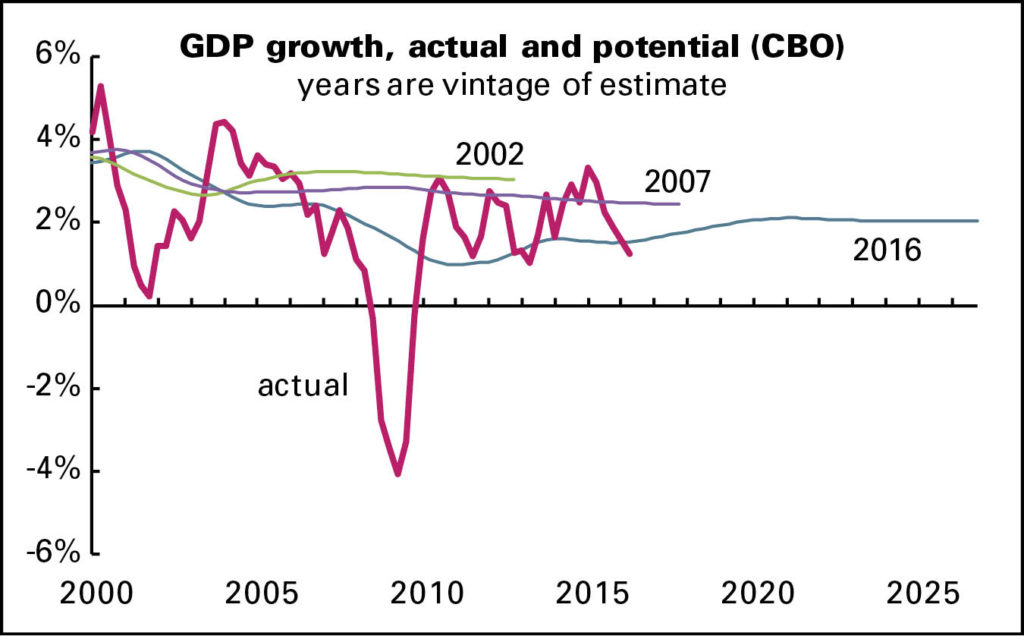

And now on to a more arcane topic, potential GDP, which is of interest mainly to economists and central bankers. In theory, when actual GDP exceeds potential, inflationary pressures mount; when it’s below potential, there’s room for accelerating growth.

But as the next graph shows, the estimates of potential are quite unstable. In 2002, the CBO was estimating a potential growth rate of just over 3%, after recovery from the 2001 recession. Despite that recovery, which exceeded 3% from 2003–2005, the CBO marked down its estimates of potential growth to the 2.7–2.8% range, even for some of the period before the estimate. Reality outdid these greatly diminished expectations by contracting sharply in 2008 and 2009. But now the CBO sees the U.S. economy has having less potential than ever; it sees the growth in potential as 1.6% now (not that reality is outdoing that by much) and rising to all of 2.0% over the next decade.

Should one actually make monetary or fiscal policy based on such projections? The glum 2016 projection is a function of slow labor force growth and weak productivity—but should we accept those, especially productivity, as the best we can do? Or should we instead be trying to figure out how to raise them?

All This, and Indentured Servitude Too

It’s no secret that many of our more vulnerable workers have it tough these days.

In July, the Treasury Department decided to take a look at the widespread use of non-competition agreements among low-wage workers as a factor in ongoing low job churn and wage growth.

Additionally, Case Western law professor Ayesha B. Hardaway is looking into the proliferation of these “non-competes” among low-wage low-skill workers as a condition of their at-will employment as a violation of the 13th Amendment. She argues that Reconstruction Era debates, legislation passed after the amendment itself, and judicial opinions of the time make it clear that the prohibitions against indentured servitude and peonage in the broader amendment were intended to prevent wage slavery.

Which is what you get if you put at-will employees on this particular one- way street. They are not protected by contracts and, since they cannot seek like similar employment elsewhere, have no bargaining power.

And therefore no economic mobility. Hardaway argues that such use is outside the original scope of post-employment restrictive covenants, which were designed to protect trade secrets, thereby encouraging employers to invest in new ideas and in the training of their employees.

Restrictive employment covenants have been addressed by the courts for centuries, and US legal thought on such matters came, originally, from British courts in the 16th century. These courts generally put attempts to restrict work opportunities of former apprentices under the rubric “improper and unethical motives of masters.” Specifically, applying the rule of reason, the court stamped the idea that an apprentice could not seek employment in the “very trade he honed during his apprenticeship to be morally improper and outside ordinary norms.” Such thinking on employment restrictions held in England, although specific confidentiality clauses, and non-solicitation and non-poaching agreements, Hardaway’s “original scope,” generally got the green light.

And so it was in America until the late nineteenth century, when judicial decisions began to wear away the precedent set by the test of reason. Even so, through the twentieth century such agreements were limited by the courts to high-level employees with access to proprietary information, employees whose names and reputations themselves often added value to the company. These sophisticated workers are on a two-way street: at the same time they sign such agreements, they also sign employment contracts.

Hardaway believes that subjecting low-wage un-skilled workers to similar arrangements “fails to comport with the established rule of reason.” Indeed, and worth thinking about with the Politics of Rage getting so much ink these days.