Stanley Fisher bravely gave a talk on labor productivity last week—bravely because Robert Solow was in the audience, which Fischer acknowledged as an honor, a joy, and something of a difficulty. In his talk Fischer touched on a number of possible measurement problems, but, like the majority of serious researchers on the topic we have quoted over the years, sees no reason to believe there has been an increase in any measurement bias, meaning the long standing decline in productivity is not a measurement problem.

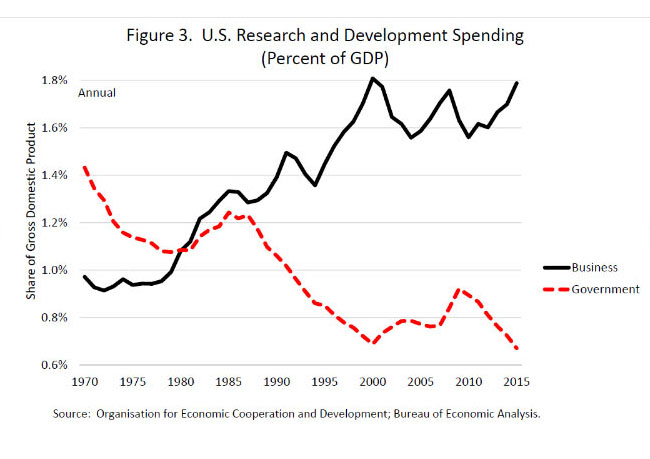

Fischer hauls out the old, and we’d say true, saw that public-sector research is responsible for the R part of the R&D pair, and the private sector is responsible for the D. This of course is a controversial statement, how many arguments have we all had on one side or the other? But the research in favor is pretty conclusive. The private sector has done wonders with the applications, but the basic materials are close to entirely produced in government or government-funded labs. (If you have evidence to the contrary, please send it along.)

That’s why Fischer calls the stunning trend shown below disturbing. We’d add it may go a long way toward debunking the idea that there’s any mystery cloaking current weakness in productivity.

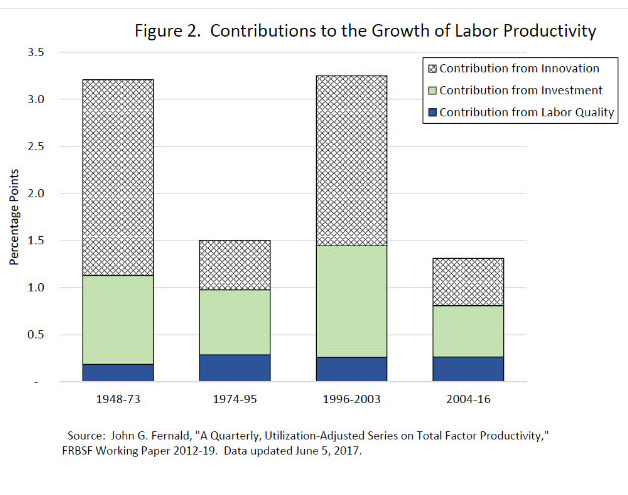

John Fernald, researcher at the San Francisco Fed who has had tremendous influence on the Federal Reserve’s overall thinking on the issue, has shown that labor’s contribution to productivity, driven by gains in educational attainment, etc., has been stable in the periods shown on the graph below, which were derived from his team’s work on the subject. Investment has been a dragging factor, but the real culprit appears to be innovation, the residual tracked by Total Factor Productivity. Somewhat elusive by nature, it’s designed to measure changes in output that cannot be explained by labor and capital. Belief in the power of that component of TFP was the Kool-aid of belief in the New Economy, but the contributions of formal and informal R&D, better management, gains driven by government-provided infrastructure (there would be no farming west of the Mississippi without federal water projects), and the creative destruction wreaked by highly productive firms on the trailers are certainly real.

While we’re not graphing this, Fernald’s research shows that productivity contributions from IT producing industries peaked between 1995-2000, the contribution of IT-intensive firms increased ten-fold between 2000 and 2004, and then shrunk back to where it had been by 2007. Non IT-intensive firms plucked their low-hanging fruit by 2007, and their contribution disappeared by 2011. Many of the revolutionary increases in productivity took place in retail and wholesale trade, and in online brokerage back then. Nothing comparable is happening now.

Fischer believes that AI, his example is self-driving cars, medical technology (gene-driven treatments), and cheaper alternative fuels all suggest that we can reach for higher fruit, and raises the possibility that we may be in a productivity lull as these advances spread through the economy. He notes that it took decades for the steam-engine to make its changes. One hopes.

the Rule of 70

And Fischer cuts to the chase. In answering his rhetorical what does this matter?, he turns to his favored measure: how long it takes for productivity and, therefore, income, to double. During the 25 years between 1948 and 1973 when labor productivity was growing at 3.25%, it took labor productivity 25 years to double (70/3.25); in the 42 years between 1974 and 2016, with labor productivity growing an average 1.75%, it took 41 years to double. What is the difference between the prospects facing the young when per capita incomes are doubling every 22 years and when they are doubling every 41 years. An excellent reason to work to shift the tide.

Noting that reasonable people can disagree on how best to advance the objective, Fischer points out that another restraining factor may be uncertainty related to government policies, which stabilized in 2013, but was on the rise again in late 2016. Damping such uncertainty by more clarity is “highly desirable—particularly if the direction of policy itself is desirable.”

Perhaps we could harness some creative destruction and dismantle our $125 billion-dollar-a-year Grid Lock industry. (Forbes noted about 56% of that is direct, wasted time and fuel while sitting in traffic.) It’s a far cry from what we hoped for from the innovation residual, but perhaps we should try to recoup the kind of productivity gains that came with the interstate highway system in the 1950s and 1960s—only maybe with some 21st century modes of transportation instead?